The Business of Public Space: Why #BoycottKunsthalleBerlin?

The recently opened private, self-appointed Kunsthalle in Berlin’s historic Tempelhof Airport faces growing backlash over purported non-consensual use of public space and city funding. Over 931 of Germany’s most eminent arts and culture professionals have signed an open letter to city officials boycotting the institution’s alleged rent-free use of two hangars and subsidised cultural senate funding, supposedly totalling over €100,000 per month.

The Kunsthalle’s opening comes months after an equally controversial exhibition in the same hangars by the same organisers acridly titled Diversity United despite an all-white, mostly male curatorial team, with financial backers including Russian President Vladimir Putin and controversial German real-estate developer Christoph Gröner, who is said to be responsible for hundreds of evictions amongst widespread gentrification of the city. Since travelling to Moscow, Diversity United has seen multiple artists withdraw in protest.

The participation of Berlin’s residents in the Kunsthalle–or poignant lack thereof–raises pressing questions over the legitimisation of public cultural projects and distribution of tax revenue. Kunsthalle founder Walter Smerling has now said he welcomes a dialogue with the city, but it may be too little too late. Undisclosed sources claim the Kunsthalle will close its doors as early as next month following a storm of bad press. The Kunsthalle has declined to comment.

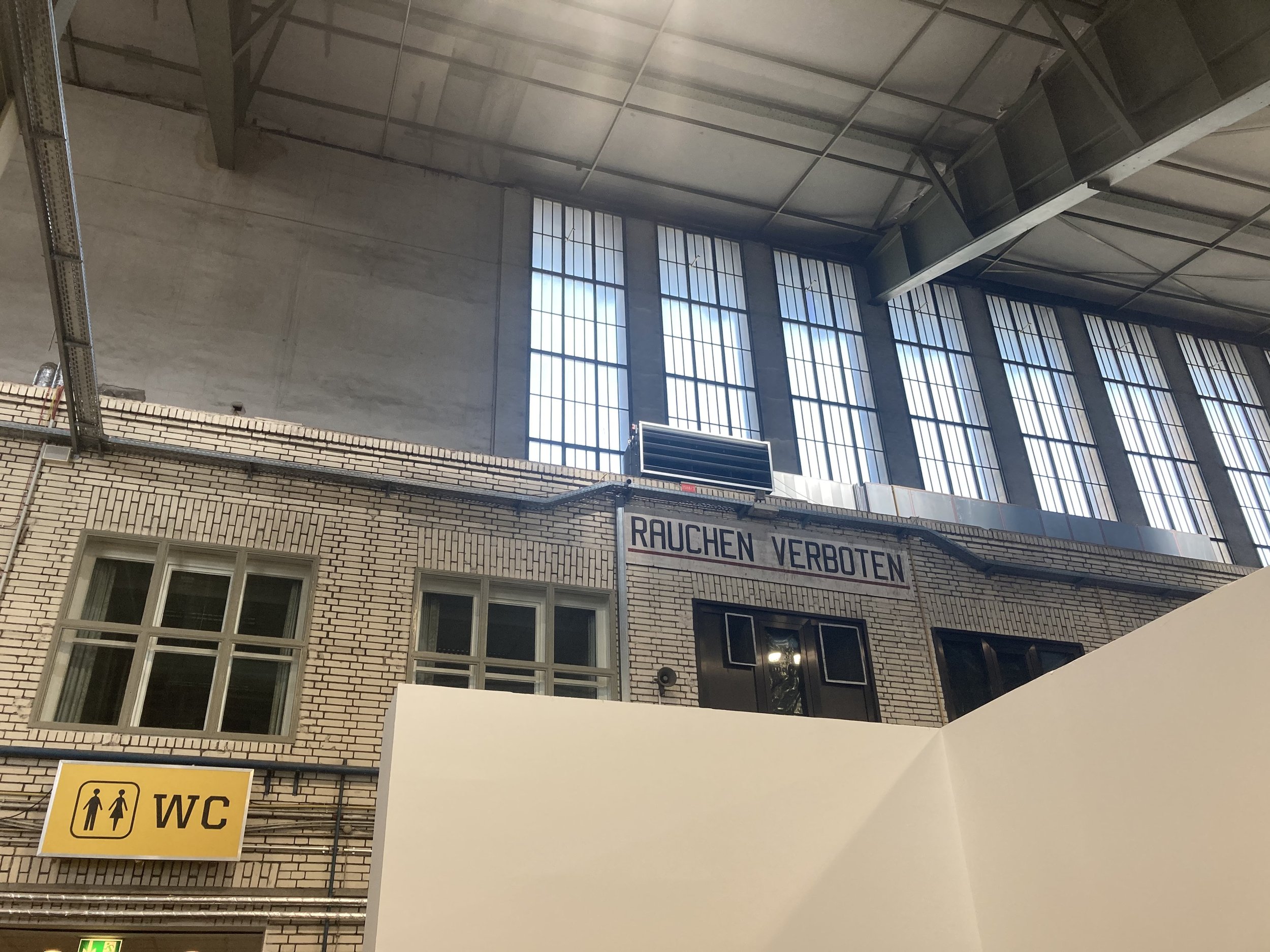

Tempelhof Airport Main Entrance. Photo by Camille Moreno.

Built in 1927 and closed in 2008, Tempelhof was one of Berlin’s first airports, with its 380 hectares of field since becoming the city’s largest public park. The building has oscillated in use; hosting conferences, music festivals, and art exhibitions. A portion of the structure was transformed into a refugee camp in 2015. In 2021, Senator for Urban Development and Housing Sebastien Scheel submitted plans for a portion of the building, including its rooftop, to become the city’s new cultural epicentre–an experimental arts and culture project for Berlin. However, renovations have been slow to start.

Tempelhof Airport had an already iconic status as the centre of the Berlin Airlift of 1948-1949. The main entrance is located at Platz der Luftbrücke. Photo by Camille Moreno.

Shortly before its opening, residents learned of a new private “Kunsthalle” - a liberally appointed title given the legacy and weight of the word referring to public or non-profit Kunstvereins or art collectives in Germany (1). When the news was leaked that Berlin had supposedly agreed to let the hangars rent-free, as well as subsidise the costs with over €2,400,000 euros over the course of a two-year lease, an open letter was sent to city officials calling for the immediate closure of the exhibition stating:

“If the founding of a serious Kunsthalle Berlin worthy of the name is preempted by arbitrary self-designation, this indicates a need for action. We, therefore, call for ethical guidelines to be developed, with regard to the relationship between the public sector and private interests or sponsors, in order to prevent such instrumentalizations from happening in the first place.”

MADE IN BED sat down with two of the boycott’s organisers, Zoë Claire Miller, bbk spokesperson, and Cléo Mieulet, a representative from Transformation Haus & Feld, an initiative that aims to transform Tempelhof’s public field through progressive and educational ecological intervention.

MADE IN BED: I feel like Berlin might be more vulnerable or susceptible, more than other cities, to being taken advantage of by culture and art washing due to how many people come here to be creative.

Zoë Claire Miller: I think that it's more vulnerable to exploitation via speculative capital particularly because it’s a poor city. Every fourth child is living off welfare, more people rent their homes rather than owning them than in most European capitals, only 17% of people here own their apartments. For decades the city was in debt and sold off public housing and land to the highest bidder. The main reason for Berlin’s susceptibility to art-washing, besides big capital’s hunger for “investment opportunities,” is political incompetence. Politicians and the city administration have a non-participatory tradition and praxis of either ignoring and thwarting meaningful civic initiatives or hijacking their work, taking grassroots ideas and concepts, watering them down and implementing them badly with no involvement of the initiatives themselves, so that their purpose is defeated but they can be showcased as a community, and sourced while decisions are made behind closed doors without consulting those affected. The portrayal of the “Kunsthalle” as a desirable addition to the Berlin art scene is exemplary of this.

Aging signs at Tempelhof Airport. Photo by Camille Moreno.

MIB: I read about the ideas that you have for the next ten years, The Transformation Haus & Feld at Tempelhof. One of my questions was just, well what should we do with Tempelhof? Because it is a really big building that takes a lot of maintenance. Is there an answer?

Cléo Mieulet: The first thing is to observe how it is governed now, and that is through a public-private partnership. The city government gives in to a profit-oriented structure. The building is owned by the city and its citizens, so a private structure can't work. That's my systemic analysis. Public-private partnerships will always give us less public space. For us, it has to be exchanged by common structures and common practice where citizens and active organising groups can co-create the development of the building at eye-level with the actors of the city or of the state. We are far from that now. There are proposals for some formats that “wash” this kind of approach, so that the state and cooperating private firm can write somewhere they have enabled participation, but nothing happens. So to start, implement a structure that is really able to enforce citizens’ participation.

Coming from the UK you might be familiar with the Climate Emergency Centre. They responded to a 2019 climate emergency action and out of their initiative, a network has grown that reclaims fossil fuel-dependent infrastructures and transforms them for the benefit of the future needs of citizens. They teach practical skills to promote a circular economy, such as gardening, reparation, and reuse of textiles. We need implementation of this circle and regional economy to answer to neocolonialism and global destruction, to get away from reliance on supply chains.

Allotment gardens in Tempelhof’s airfield. Photo by Andreas Prost. Courtesy of Deutschlandfunk.

MIB: I'm interested in the role of ecological initiatives and how they play into using this space. Looking at the Tempelhof field is almost the polar opposite of what is going on inside the building. Like if you didn't know about any of this, you could go to Tempelhof, the outdoor part, and see everyone flying their kites, making their gardens, and kind of being blissfully unaware of all this.

CM: Yeah, when you look at it on the surface. When you live in the city, for example, there are also background problems with the field. There was a Volksentscheid (type of referendum) there–a German process which is a form of a petition that is legally binding–that made the field open to the public and prevented it from being built on–which the SPD, the biggest party in Berlin, would love to do. They would love to turn it all into lofts and offices. The SPD is still blocking the implementation of more gardens.

Tempelhof airport and airfield. Photo by Christo Libuda. Courtesy of Lichtschwärmer.

It looks so nice, but it would be very intelligent to have larger parts of the area have permaculture, but when you apply for doing something as a civil actor on the field you’re only allowed a maximum of three years and it must be able to be removed, so you can't plant any trees. You can't plant any bushes. It's forbidden. And that's only for the sake that they, one day, do get the permission to develop it all with new builds. I think that the former airport structure could be a valuable site for transformation, where citizens could learn skills to be self-sufficient in a safe, cultural space.

ZCM: Space is urgently needed in Berlin, especially for art studios. We have a huge housing crisis, but also an extreme lack of affordable space to rent for creative production in the city, while Tempelhof and other massive public properties languish, largely unused.

An empty gallery in Hangar 3 at Kunsthalle Berlin. Photo by Camille Moreno.

There’s also an issue of inflexibility in the procedural logic of public property development. For instance, the whole former Tempelhof airport building is listed. The Nazis did a shitty job building it. It looks solid from the outside but on the inside, all of its infrastructures need to be completely renewed. Since it’s listed, it has to be renovated and repaired to its original state, which of course raises questions, both in terms of sustainability and utility. These gigantic hangars were made for aeroplanes. Their size and structure are not well-suited to current needs and potential uses. They’re being renovated at great cost, but for what? Do we need them at all? Wouldn't it make more sense, for instance, to re-wild at least one of them and let the foxes and birds in?

The Kunsthalle Berlin in Hangar 3. Photo by Camille Moreno.

MIB: Do you think that part of the building should go?

ZCM: I think that it would definitely be interesting to see about allowing at least one hangar to become a transitory space between inside and outside, between nature and a built environment. But we also know that even the renovation as currently intended is not a high priority for the ruling coalition. Progress is slow, the statement on the THF website about the building being/becoming a space for Berliners, culture, and experimentation stands in crass contrast to what is actually happening there, which is very, very little.

CM: You can also go into the hangar and take modular parts and transform it that way. But for that, you have to have an opened Denkmalschutzbehörde or office for [historic] listed buildings. That's a whole discussion in Germany in general with the listed spaces. They are really against any transformation of [historic] buildings.

Tempelhof Airport Hangars. Photo by Camille Moreno.

MIB: Is the three-year rule on the field the historic preservation, or different legislation?

CM: No, it's not historic preservation for the field. It's political decisions that are playing on the open site.

MIB: The fact that they can't put any trees is terrible.

Berlin police are the airport’s longest-standing tenants. The Tempelhof Police Headquarters would cost €280 million to renovate, which could be more expensive than building new. Photo by Camille Moreno.

ZCM: Who exactly decided this? When and how? What's the political organ that is in charge of this? Parks commission?

CM: Yeah, Grün Berlin GmbH, also a public/private partnership. Grün Berlin is also an enterprise that is ruling all the green spaces in Berlin, so they also have this aim to make money. They privatised the Britzer Garden, for example. Now it's one of the gardens where you have to pay for entry.

MIB: I went to the Prinzessinen Garten today. It's still there, but not quite what it used to be.

CM: It shrank.

ZCM: They were only offered a graveyard in Neukoelln as a substitute for their old location, so now they're in a graveyard. It's quite difficult to dig and plant vegetables in a graveyard.

CM: Carrots out of zombies!

ZCM: These are the kinds of compromises that are offered to amazing civic initiatives in this city.

MIB: How about Floating University? The ecological and educational transformation and art project that built wooden platforms inside a rainwater retention pond next to the airport. They filter water, study biodiversity, and host art residencies.

ZCM: For quite a while they were in limbo about getting their rental contract renewed by Tempelhof Projekt GmbH, the public company that is in charge of developing the former airport, and had faced a lot of opposition from other city departments. Now, luckily, they are safe for a while, for this year at least. They are also part of the Transformation Alliance THF, which formed as a reaction to the Kunsthalle scandal to demand transparency and actual participation in the building’s development and use. Floating University is a model project of nature-oriented, collaborative, communal, collective modes of work in alternative education, experimentation, and worlding.

One of Floating Berlin’s many outdoor structures. Photo by Camille Moreno.

MIB: It seems like it's about so much more than just these hangars or the field or even this airport because it's kind of about setting a precedent for what will continue to happen with public spaces. Where do you draw the line?

ZCM: It's part of a larger picture–fighting back against dysfunctional policies endangering the city as a space for all people, not exclusively the wealthy. The ongoing resistance to displacement, privatisation, and corruption, and the concept of public-common partnerships versus public-private partnerships.

CM: And art and ecological transformation share the same rule that their primary function is not to generate profit.

ZCM: The creative industries are a huge industry that does generate a lot of profit, but the arts, in a narrower sense, are largely based on self-exploitation.

Germination initiative: Floating invites visitors to take home a packet of seeds and grow them on their windowsill. In a cooperative action at the end of May, the seedlings are returned and planted collectively at the site. Photo by Camille Moreno.

CM: I think it's a repetitive pattern though, with the cultural development and the necessary ecological development of cities and spaces where people live very close together. Anything that is not producing profit is getting pushed out. So we have an increase in prices. That's the general diagnosis again and again.

MIB: The reason I asked about Berlin being susceptible to being taken advantage of is this impression people have of “poor but sexy.” I don't know that Berlin actually wants to be poor but sexy.

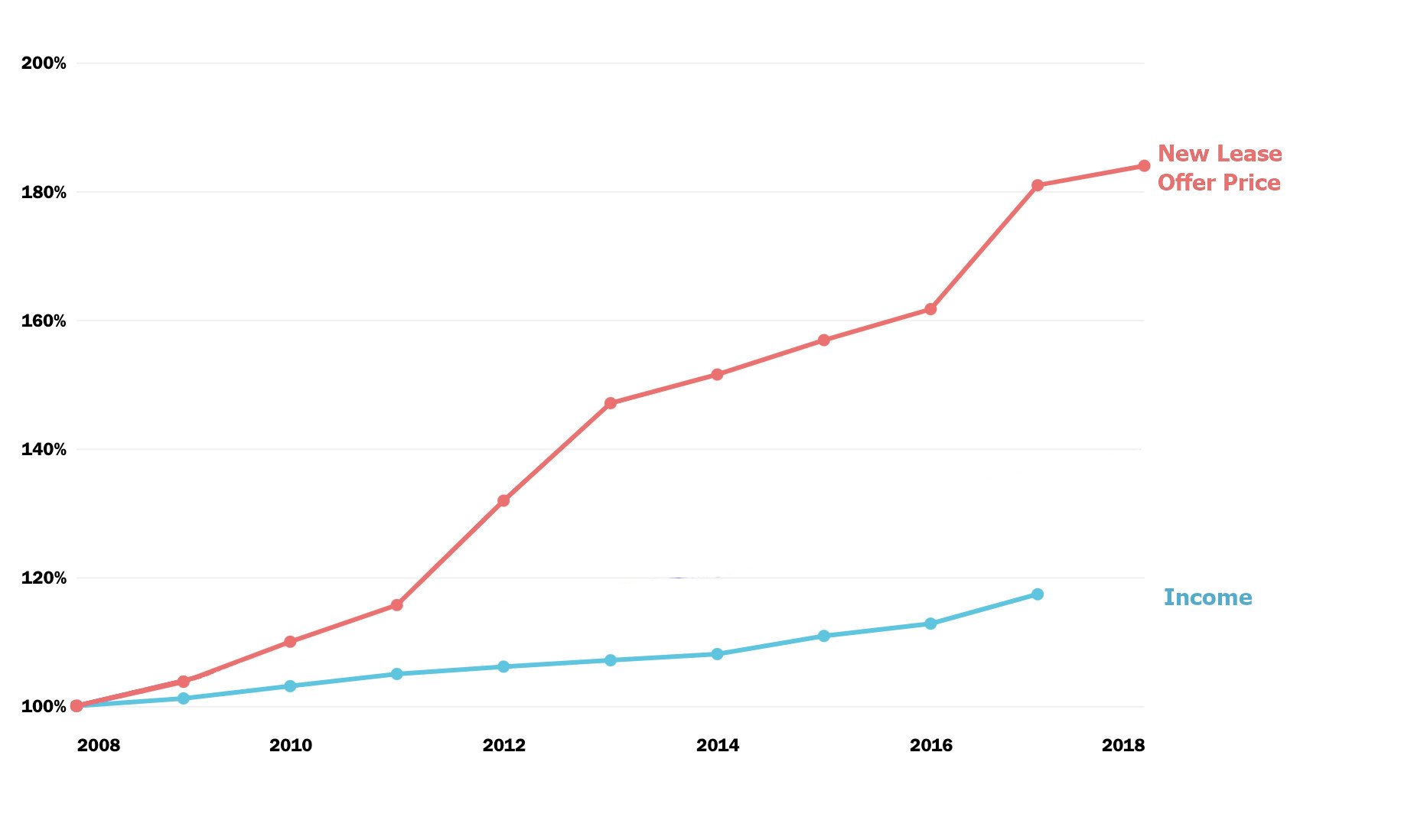

ZCM: We're already far past “poor but sexy.” It's really awful for the future of the city that the lack of affordable housing means that now young people can only move here if they come from wealth.

Berlin median income versus new rent contracts from 2008-2018. Chart: Tagespiel. Translated and adapted by Camille Moreno. Source: IBB Wohnungsmarktberichte, Mietspiegel, Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen, Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg.

MIB: That's why I'm concerned. Coming from London, this financial megacity where working artists have steadily been priced out. Obviously we have an active art market and higher salaries than Berlin, but we don't have that level of production that you have here or the pace to go along with it, but if Berlin stays on this track, I don't know whether the city will be able to continue to produce that way.

ZCM: It won't be able to, and this has been something that artists have been warning about for many years. There's this thing called the Coalition of the Independence Arts, which is basically the shared interest alliance between all the artistic fields–visual arts, performing arts, literature, music–and had this slogan for asking for more structural funding and changes in policy over ten years ago: “Spirit is even more fleeting than capital- hold on to it!”

This is something that everyone who’s a cultural producer is extremely aware of, but our politicians seem disengaged and unwilling to make the policy changes that would need to happen. For instance, the wildly successful campaign for expropriation, “DW & co Entgeignen,” was a petition for the expropriation of the largest landlords and the recommunalisation of their properties: in sum, 60% of the housing in the city. More than one million Berliners voted for it and far more votes were cast in favour of the petition than for our current mayor. She’s on the far right-wing of the centrist party SPD, and a declared opponent of recommunalisation, so she’s doing everything possible to keep it from happening, although the petition is legally binding.

MIB: It's like theatre.

ZCM: Yes, so a really hot topic or keyword here in Berlin is “sham participation” which is basically false or supposed participation. There have been so many supposedly participatory processes for the developments of different public properties, Tempelhof airport, and their cultural uses. Most recently Alte Munze, and it also happened around Hermannplatz where there's a big conflict around gentrification–fuelling development plans of a private investor. Every time the majority takes part in these “participatory processes,” citizens and residents end up feeling ripped off because the city hires agencies to create results that they want, which were fixed from the beginning, rigged.

Bernar Venet’s solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Tempelhof. Photo by Camille Moreno.

CM: I think they reproduce this theatre very often in Berlin because we have a population that is very progressive and there is pride in the history of the 80s–occupying the houses, creating spaces for culture and the development of participation and openness for people who are not driven by money all the time–so they have to include sham processes of participation.

MIB: Like to appease them and go through the motions?

CM: It's part of the story to include the culture.

ZCM: And then they can proceed with the results which were fixed from the start and claim that they have the stamp of public approval because of the so-called participatory process.

MIB: So in terms of Smerling, the boycott started before the Russian sanctions but now has a new layer in terms of the Moscow exhibition and ties to Putin.

ZCM: The boycott started when the Kunsthalle opened, in the same space where the Moscow show had been first, so that's how Smerling got his foot in the door. The show that's there right now is a solo of an old buddy of his, an extremely wealthy, old French artist, so obviously he wasn't going to support the boycott. That's why the main way artists were showing solidarity was by removing their works from the show in Moscow.

Signage for Bernar Venet at the Kunsthalle Berlin. Photo by Camille Moreno.

At the same time, even three or four years ago, when the exhibition Diversity United was conceived, it should have been obviously questionable as to whether having Vladimir Putin as a patron was a good idea. Such an immoral decision ties into the German policy of appeasement towards Putin and its authors, like Gerhard Schröder and his protegé Walter Steinmeier, the current German President and the other patron of the show. The legacy of the “great coalition,” the GroKo (SPD & CDU)? Decades of bad decisions that made Germany completely dependent on Russian fossil fuels.

We also spoke with Ukrainian artists who were invited to show works in Diversity United. One of them was already far along with planning when he received the information, in very fine print, that Putin was going to be a patron of the exhibition. He questioned the decision and got no answers from the curators. I think it’s a question that curators have to ask themselves, how could think this was okay? They obviously were paid well, but the artists were not paid any fees at all.

Walter Smerling hadn’t paid artist fees to any of the exhibiting artists and they were complaining to us, because Berlin has minimum wage standards for artists, although they’re only legally binding for shows that get public funding from the city-state of Berlin and not the federal government. His show got around €2million from the Federal Foreign Office with no strings attached in terms of paying the artists for their work. Even recently in interviews, he was still evading the question about whether artists should get paid for their work.

MIB: Those pictures of the Diversity United opening were really ridiculous. All the white men–really silly looking. How could they not have thought about that?

ZCM: His artistic vision is that of the patriarchal Derriere Garde. He did not see the irony I am sure. He’ll name drop terms like feminism and diversity. His next show might be called Ecology Unified but it would certainly not conceptually engage with what the word means.

The opening of "Diversity United" in 2021. Photo by Bernd Von Jutrczenka. Courtesy of Alliance/DPA/AP Images.

MIB: And you didn't hear about the Kunsthalle opening until basically right before, right? How did you learn about it?

ZCM: I spoke with Niklas Maak, the journalist who broke the news for the FAZ, before his article was published. He broke the news of the Kunsthalle opening and then that an astonishing amount of people involved had been misleading or lying about the terms of the deal, like several politicians and Tempelhof Projekt staff. He wasn’t only getting the hangars rent-free, it was also agreed that the city would fund 50% of the utilities, which the Senate Department of Finance estimated would be €100,000 monthly.

MIB: Have you received a response to the open letter?

ZCM: There were many responses on a national level, the who’s-who of the German art scene signed it. None of the people who were addressed answered. There was no reaction from any of them.

MIB: What's the next step if you don't receive one?

ZCM: We’re planning to call for the use of the space as a commons once Smerling is out at the end of May. We want things happening there that make sense and reflect the public interest and the current discourse that is actually relevant to the world and our city.

Hangar 2, Kunsthalle Berlin. Photo by Camille Moreno.

MIB: Since the open letter, I read that Smerling made a statement that he's happy to have a discussion.

ZCM: Yes, he would have been happy to have a discussion, but we are familiar with the tactics of claiming a conversation and gaining approval and saw no common moral grounds as a basis for conversation. Nothing could have been achieved other than good optics for him. He was obviously very desperate, he was very unprepared for the shitstorm that his latest enterprise caused, and did not see that coming. It was always clear to those criticising the gift of these public resources to him that engaging in conversation would not make sense for us as members of the Berlin art scene, because he’s not the problem, he’s just a symptom of a disease.

MIB: The tip of the iceberg?

ZCM: Right. The fact that he was able to exploit the space and these public resources is the fault of a lack of oversight and general concept on the part of our politicians.

MIB: I just don't want Berlin to become London, it's a different city for a reason.

ZCM: That's what we're all afraid of. With Elon Musk now in town because of his Tesla factory in Brandenburg, talking about what a good time he had at KitKatClub after not being let into Berghain, you can only imagine what he might want to buy here. The Amazon European headquarters is being built right now in Friedrichshain, a traditionally leftist and historically working-class neighbourhood.

CM: And Google…

ZCM: And that after so much resistance, Kreuzberg put up a massive fight against a planned Google Campus, and Google wasn't able to have the real estate they wanted to.

Raised rent prices in Munich versus Berlin from 2010-2020. Source: statista/immowelt.de│Colourbox/Kanate Chainapong.

MIB: So for now he's out in May and then you have your next step.

ZCM: We're approaching politicians and asking them to support our plan. If they say no, then we will try to use public pressure to make it happen.

CM: We have named the campaign “Liberate THF” inspired by Liberate Tate.

ZCM: So far there are around ten different initiatives involved in it, but it’s all very new, so more and more initiatives will be joining.

CM: It's also about learning from other initiatives that failed before us, and establishing common public partnerships at the very beginning as well as taking care that you don't sign a contract that you will regret afterwards, perhaps because the structures behind them hadn't been built before or been made transparent. I don't know if there are many projects before us of that size that were built on the cooperation of activism, like real climate activism as well as the art and cultural worlds together.

ZCM: A key takeaway from this scandal is that we’re not going to put up with this type of non-transparency and cronyism anymore. The art scene has clearly stated its resistance in a unified voice and we know that public opinion is on our side. There is not much ambiguity here. What happened was scandalous and inexcusable.

CM: The other last thing is that change needs resources. It doesn't work that Lufthansa gets [bailed out] at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, and we are always begging for the most important transformation we need now. It's a question of who we are taxing. Fossil fuels are bound with art and it's all connected. We have to be much more direct. It's time to get angry.

ZCM: When the people come together it’s impossible to ignore them and stick with business as usual. Berlin has a strong tradition of self-organisation and resistance and continues to live up to that history.

Photo: @berlin.banners

MIB: I'm so grateful for what you two are doing.

ZM: And you're studying at SIA? Is that about becoming an auctioneer?

MIB: It's actually not really connected to the auction house. A lot of people get the wrong idea when they hear the name ‘Sotheby's’ because they think, “oh, money, corporation,” but that's why I wanted to write this article. A lot of our readers are based in London and likely don't know anything about this mess. They're usually coming from a more commercial perspective. We talk sometimes about preaching to the masses, I think it's also important to disseminate information to people who wouldn't otherwise have had a chance to learn about it.

ZCM: There is currently a lot of discussion around the important role art plays in undermining sanctions, and in money laundering, tax evasion…moral considerations need to play a bigger role in the art world in general.

MIB: Absolutely, and everything's connected like you were saying. It's an environment, the art world.

ZCM: Definitely. I hope many different members of the art scene are reconsidering how open they are to very dirty money and questionable concepts based on the Walter Smerling story.

Thanks to Zoë Claire Miller and Cléo Mieulet on behalf of MADE IN BED.

To support the boycott, follow #boycottkunsthalleberlin.

Sources:

(1)Artnet, Morgenpost, e-flux, Tagespiel, Bruegel, Bricks, Koalition der Freien Szene Berlin, Bpigs, Arts of the Working Class, Monopol, and FAZ.

Camille Moreno

Features Co-Editor, MADE IN BED