Healing the Past and Dreaming the Future: Indigenous Art in Latin America

Indigenous Latin American Artists are making important contributions to the arts, reclaiming a buried past and reimagining a different future. These artists continue to search for self-determination as they remain confined, literally and metaphorically, to the margins of the art world. The need for recognition and protagonism in the narrative of art history is a struggle, especially for those artists that identify with and stand for indigenous communities.

More recently, institutions around the world have opened their doors and created spaces for the expression, autonomy, and representation of artists of indigenous descent. These artists have thus begun weaving invisible webs that link them to one another, using their art to protest social, cultural, political, and environmental causes from a deep-seated place of dissent. United against the exclusion, erasure, and misrepresentation of indigenous voices, it is worth highlighting two artists: Cecilia Vicuña and Ernesto Neto and the institutions that feature their works. These institutions are, by extension, celebrating authentic and marginalized forms of artistic expression.

Cecilia Vicuña, Living Quipu, 2018. Performance. Brooklyn Museum, New York City. Photo Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin.

The works of Neto and Vicuña are inseparable from the history of indigenous populations in Latin America. In the 1930s, the movement of Indigenismo called for a recognition of indígenas as citizens, exposing years of exploitation that reduced them to nothing more than '“savages.” [1] The movement aimed to dissolve outdated colonial hierarchies, bestowing upon indígenas a renewed sense of community and self-sovereignty. This cultural awakening laid the foundation for contemporary Indigenous artists who use their art as a channel for protest and representation.

Sadly, Indigenous Latin American art is chronically underfunded, often swallowed by Contemporary departments to keep it afloat. It is interesting to draw parallels here between Latin American Indigenous art and the Aboriginal art movement, as the latter has successfully established itself as an independent, self-sustaining category. Big name collectors have taken interest in the works of Aboriginal artists and major auction houses like Sotheby’s have held auctions exclusively for Aboriginal art. Is it unrealistic to envision the same for Latin American Indigenous artists?

The inclusion of indigenous art and artists within their own category raises several problems. For one, the wide number of indigenous populations complicates their categorization within a single grouping (in Ecuador, the Quichua alone contains 17 subgroupings). [2] The term indígena can also be considered problematic given its historical connotations. The art world too easily falls prey to the tendency to associate or mislabel Indigenous artists and their art as “native” or “primitive.” [3] Individual artists have thus made it their mission to dismantle these cultural and social barriers, finding ways to situate indigenous art alongside other big contemporary names.

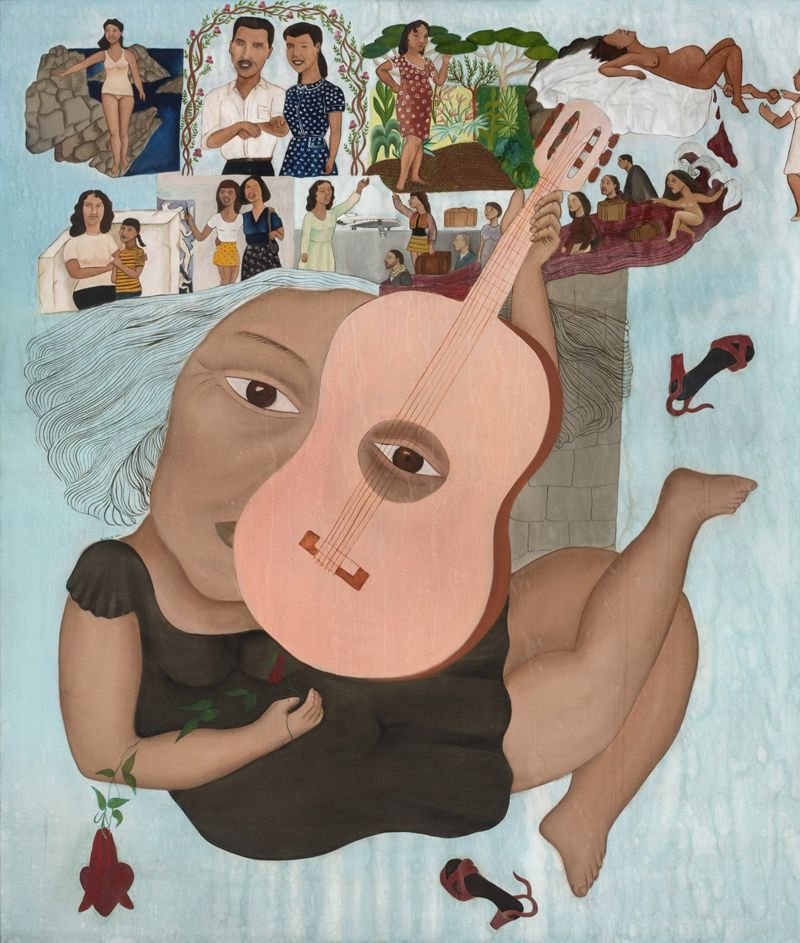

Cecilia Vicuña is one of these artists. Soñar el Agua, the largest show of works by Vicuña, is currently making its way around South America, in a partnership between the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes (MNBA) and Fundación Arte Precario Cecilia Vicuña. Inaugurated at the MNBA in Santiago, Chile earlier this year, the exhibition is currently at Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Malba), Argentina and will travel to Pinacoteca in São Paulo, Brasil later this year.

Soñar el Agua is a celebration of the work of the Chilean artist, poet, and self-proclaimed feminist. Vicuña was born to an indigenous mother; it is her upbringing that feels the most pertinent in her artistic production. The show spans the length of her career, including sculpture, poetry, performances, paintings, photographs, and installations. Curated by Miguel A. López, Soñar el Agua is a celebration of an ancestral past and a look into a progressive future of environmental consciousness, equality, and self-determination for the indigenous populations.

Vicuña is the first Latin American woman to have held a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Her work in documenta 14 was the most reproduced of the show and in 2022, she received a commission for the Turbine Hall and The Golden Lions for Lifetime Achievement Award. [4] Vicuña’s recognition in major global art centers and highly trafficked art events is a testament to the advancement of Indigenous art — especially given the history of neglect of indigenous populations. Vicuña’s accomplishments have leveled the playing field not only for women artists, but for Latin American Indigenous artists as a whole.

Cecilia Vicuña Becomes the First Chilean Woman to Receive The Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement Award, 59th Venice Biennale The Milk of Dreams, April 2022. Source: artealdia.

Following Vicuña, Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto is carrying out a mission of his own in his participation in Remedios: Directions to the Old Ways, a show featuring the works of 20 artists from around the world. The exhibition is a collaboration between C3A Centro de Creación Contemporánea de Andalucía and Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary held in Córdoba, Spain.

For over a decade, Neto has worked closely with the Huni Kuin, an indigenous group of the Amazonia. [5] In Remedios: Directions to the Old Ways, Neto showcases BasnepuruTxanaYube, a handwoven web that hangs over the ceiling, expanding into an immersive, sacred space where individuals gather in communion. The work was first introduced in 2015. [6]

Ernesto Neto, BasnepuruTxanaYube, 2015. Installation for Remedios: Directions to the Old Ways, 2023-2024. Photo Courtesy: Imagen Subliminal. Rocío Romero + Miguel de Guzman.

The exhibition’s location in a country known for its imperial history contributes to this need for rewriting the past through the decolonization of art: “Córdoba simboliza la idea de lo que pudo haber sido otra Europa.” / “Córdoba symbolizes the idea of what could have been another Europe.” [7]

Vicuña and Neto both recognize the efforts of international institutions in creating spaces for indigenous voices. Vicuña, in an interview with Carolina Castro Jorquera, mentioned that in her home country of Chile, “aún no ocurre esa mirada descolonizadora” / “we are still under the guise of colonization.” [8] It is her international ethos that has permitted her to tell the story of Indigenismo. For context, indígenas make up around 11% of the total Latin American population. [9] By presenting Soñar el Agua in national museums like Malba, Vicuña is uniting Latin American countries in a shared appreciation for their self-identity. Notably, the exhibition also marks the 50th anniversary of the coup d’etat that inaugurated Pinochet’s dictatorship. [10] Nodding to this history, Vicuña acknowledges a troubled past but reimagines a future where art and artists are no longer buried under the political instability and corrupt leadership structures that plague Chile and most Latin American countries.

Neto refers to the landscape of Remedios as follows: “estábamos trabajando en un campo de mucho rechazo, pero hoy el panorama es mucho más abierto” / “we were working in a space of significant rejection; today, the panorama is much more open.” [11] This rhetoric of hope offers a glimpse of a future where marginalised voices have a rightful place in the art world.

Last year’s 35th Biennale in São Paulo was also a step in the right direction. The Biennale featured the works of a number of Brazilian and Latin American artists like Sonia Gomes, who exercised their own form of activism in favour of indigenous populations, joining in the fight for human rights, opening up conversations around eco-activism and engaging in an anti-colonialist discourse. The Biennale helped legitimize the efforts of these artists in closing the margins, earning them a platform from which to disseminate their message. [12]

Sonia Gomes, Sem título (serie Pano), 2023. 35th Bienal de São Paulo. Source: Levi Fanan, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo.

While artists like Vicuña and Neto are making significant progress in setting the stage for a more open discourse around indigenous and indigenous-related art, there is still a lot of work that needs to be done. The fact that Neto’s work A Sacred Place, staged at the 57th Venice Biennale, provoked great controversy among critics and audiences for its primitivist subtexts is an indicator of this. [13] Issues like these raise another layer of concern in the search for an indigenous identity in the art world, that is, the danger of the select few representing an entire population. While the concern is valid, this has proven to be the only avenue by which art comes to be recognized: outstanding individual artists breakthrough leading to a bandwagon effect that can become a grassroots movement. This has happened with minorities time and time again, take Frida Kahlo or Georgia O’Keeffe for example.

Significant progress has been made. Vicuña and Neto stand alongside contemporary art giants and others are sure to follow. When they do, telling the story of indigenous art will no longer be the responsibility of the select few. Let us not forget that artists have a say over which stories they wish to tell, the way they are told, and where they wish to tell them, but they have no control over how they are received. Their hope is to be heard, and the voices of Vicuña and Neto are loud.

Footnotes:

Guillermo De la Peña, “Social and Cultural Policies Toward Indigenous Peoples: Perspectives from Latin America,” Annual Review of Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2005): 719. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-cultural-policies-toward-indigenous/docview/199820699/se-2.

Donna Lee Van Cott, "LATIN AMERICA'S INDIGENOUS PEOPLES," Journal of Democracy 18, no. 4 (2007): 130. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/latin-americas-indigenous-peoples/docview/195551184/se-2.

Guillermo De la Peña, “Social and Cultural Policies Toward Indigenous Peoples: Perspectives from Latin America,” Annual Review of Anthropology 34, no. 1 (2005): 734, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/social-cultural-policies-toward-indigenous/docview/199820699/se-2.

Jacoba Urist, “Who Is Cecilia Vicuña, and Why Is Her Art Now Receiving So Much Attention?” ARTNews, June 29, 2022, https://www.artnews.com/list/art-news/artists/who-is-cecilia-vicuna-chilean-artist-1234632890/casa-espiral-spiral-house-1966/; Cecilia Vicuña, “CECILIA VICUÑA:’“MI ARTE SE BASA EN LA IDEA DE QUE LA BELLEZA Y LA JUSTICIA DEL INTERCAMBIO PUEDE TRANSFORMAR LA REALIDAD,’” interview by Carolina Castro Jorquera, ARTISHOCK, June 26, 2021. https://artishockrevista.com/2021/06/26/cecilia-vicuna-entrevista-2021/

Lucas Mendez Chico-Alvarez, “Ernesto Neto: El artista chamán protector de los indígenas y protegido por los coleccionistas,” El Independiente, November 10, 2023, https://www.elindependiente.com/tendencias/arte/2023/11/09/ernesto-neto-el-artista-chaman-protector-de-los-indigenas-y-protegido-por-los-coleccionistas/

“Remedios: Directions to the old ways,” TBA21, https://tba21.org/Remedios2EN; Lucas Mendez Chico-Alvarez, “‘Remedios:’ el arte contemporáneo busca en el pasado las respuestas para reparar el futuro,” El Independiente, September 25, 2023, https://www.elindependiente.com/tendencias/arte/2023/09/25/remedios-el-arte-contemporaneo-busca-en-el-pasado-las-respuestas-para-reparar-el-futuro/

Lucas Mendez Chico-Alvarez, “‘Remedios:’ el arte contemporáneo busca en el pasado las respuestas para reparar el futuro,” El Independiente, September 25, 2023, https://www.elindependiente.com/tendencias/arte/2023/09/25/remedios-el-arte-contemporaneo-busca-en-el-pasado-las-respuestas-para-reparar-el-futuro/

Cecilia Vicuña, “CECILIA VICUÑA:’“MI ARTE SE BASA EN LA IDEA DE QUE LA BELLEZA Y LA JUSTICIA DEL INTERCAMBIO PUEDE TRANSFORMAR LA REALIDAD,’” interview by Carolina Castro Jorquera, ARTISHOCK, June 26, 2021. https://artishockrevista.com/2021/06/26/cecilia-vicuna-entrevista-2021/

Donna Lee Van Cott, "LATIN AMERICA'S INDIGENOUS PEOPLES," Journal of Democracy 18, no. 4 (2007): 127, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/latin-americas-indigenous-peoples/docview/195551184/se-2.

Mercedes Ezquiaga, “El universo poético de la artista chilena Cecilia Vicuña: hacer visible lo invisible,” eldestape. December 6, 2023, https://www.eldestapeweb.com/cultura/argentina/el-universo-poetico-de-la-artista-chilena-cecilia-vicuna-hacer-visible-lo-invisible-202312615440

Lucas Mendez Chico-Alvarez, “Ernesto Neto: El artista chamán protector de los indígenas y protegido por los coleccionistas,” El Independiente. November 10, 2023, https://www.elindependiente.com/tendencias/arte/2023/11/09/ernesto-neto-el-artista-chaman-protector-de-los-indigenas-y-protegido-por-los-coleccionistas/

“Choreographies of the impossible.” 35th Bienal de São Paulo. https://35.bienal.org.br/en/participante/sonia-gomes/

Camila Maroja, "The Persistence of Primitivism: Equivocation in Ernesto Neto’s A Sacred Place and Critical Practice," Arts 8, no. 3 (2019), https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030111

Francisca Gomez

Agents of Change Co-Editor, MADE IN BED