Edging Closer to Mainstream: Fractional Ownership in the Art Market

In the last decade, interest in fractional ownership and its opportunities have escalated massively in the art world. For centuries, since the idea of art investment emerged, only wealthy or high-net-worth (UHNW) collectors could invest in art by buying it physically. This characteristic protected the secretive, elusive nature of the nineteenth-century Paris Salon culture, which is similar to the culture of art investment that would come centuries later. But nowadays, thanks to the advancements in technology and the wisdom of future-looking people and art enthusiasts, things have started to change.

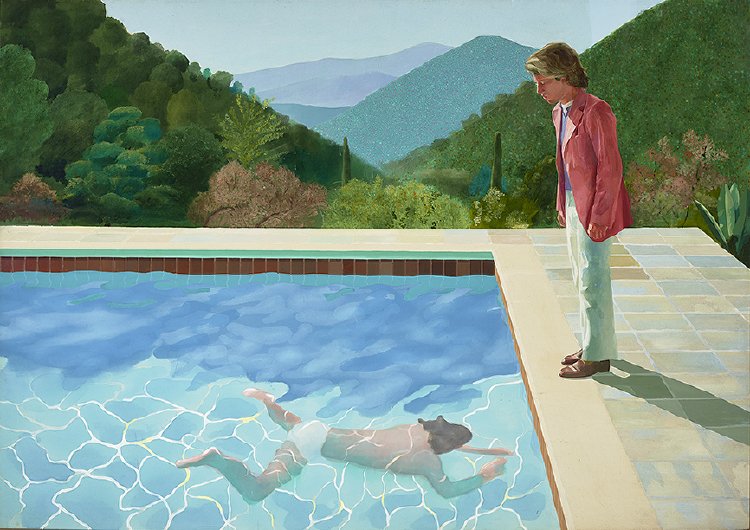

David Hockney, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972.

Presently, there are many fractional ownership companies all around the world, including Germany, South Korea, Turkey, the US and the UK. Other than the classic profit-aimed structure of capitalism, the main goals of these companies are to open the doors of art investment to the masses, democratise the market from an economic perspective and let the people have ownership in a Pablo Picasso, a Jean Michael Basquiat or maybe in the future a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci.

Fractional ownership is a novel and popular method of investing in art, where people could participate in the ownership of the artworks as low as paying between $1 - $500 USD. In finance, this method is like owning stocks or shares in real estate, where the investor does not fully own the company but owns a percentage of it.

Compared with classical ownership of an artwork, people who invest in the art as an asset class do not acquire the artwork physically to hang in their living rooms and enjoy them in their family’s presence. Therefore, the investors of Modern and Contemporary works don’t have the chance to enjoy their art physically and emerge themselves in their aesthetic properties. Instead, the artwork is stored in a secure facility waiting for it to be sold and then relocated to its new owner.

When the opportunities for fractional ownership investing in the artworks became a reality, many people in the art world started comparing ownership versus the aesthetic value of the works. For many people seeing the work in their homes or private spaces is very influential in educating their knowledge about art history, aesthetics of the work and the political or perhaps philosophical background of the stories. On the other hand, people who started investing in art either want to diversify their portfolios or be the one that owns a small share of ownership of one of the praiseworthy works in the history of visual arts. It is vital to note that a blue-collar or white-collar worker cannot own an oil painting by Salvador Dalí or Willem de Kooning within their budgets. Unfortunately, staggering art market prices have made owning a painting by these artists nearly impossible for the wider audience.

Advantages of investing in artworks by fractional ownership come in three different features. Firstly, investor of these works utilises the chance to invest in the 67.8 billion dollar art market and diversify their portfolios. Moreover, the art market has a low correlation with traditional assets such as bonds and stocks. In recession times, this results in blue-chip works holding up in value and protecting the investor from having many losses when markets are going up and down frequently in a short time frame.

Secondly, the owner of the fractional shares does not have to deal with any insurance, conservation, logistics and storage costs by themselves as it comes with owning a physical work. In the art of collecting works, this starts to be a headache for art lovers, but in the case of investing in fractional ownership, collectors do not need to worry about these negative side effects.

Thirdly, fractional shares help people to commodify something that they cannot fully possess in the first place: million-dollar works that have graced the pages of the New York Times, bought by celebrities and most importantly, have been featured on social media platforms used by millions of people every day. However, this type of commodification has always found its presence in Art History; for example, a landlord or a monarch would showcase their wealth within their home, as shown in Robert Braithwaite Martineau's The Last Day in the Old Home (1862) or Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), or a sultan introduced their exotic harem of women in Juan Giménez Martín The Sultan’s Favourite (no date).. In this case, these historical examples highlight how one now has more readily available power to buy something that once was unreachable.

On the other hand, there are several unfavourable sides to the story. Firstly, although these firms have millions of dollars of backing, their business is ultimately risky. Many companies in recent history have tried to create investment funds but failed for various reasons, including the lack of regulation, slow technological framework or wrong investment decisions about the artwork portfolio.

Secondly, numbers promoted by fractional ownership firms and closed-end art funds about the annual returns are up for debate. The majority of them consider the annual returns of contemporary art to surpass the returns of major US and international stock market indexes in the long run. But this view is highly controversial because of the survivorship bias, the illiquid nature of the art market and time period selection.

Furthermore, because of the severe lack of index fund structures, fractional ownership opportunities in the art world come with riskier prospects compared to investing in a pool of artworks simultaneously. According to ArtTactic’s recent report, since 2007, more than 200 works in the US and more than 540 works in South Korea have been fractionalised by the funds and offered to the art world enthusiast. Nowadays, someone could hypothetically invest in a small number of artworks concurrently, but investing in 50, 100 or 1000 works at the same time is still impossible. Nevertheless, these companies apply crucial fees to their customers regarding management fees and expenses. If the index fund structure transfers itself from the stock market to art world investing, fractional ownership could be fundamentally less risky and less expensive than it has been. And in a historical sense, it could revolutionise art investing like the commercialisation of index investing did on Wall Street back in the 1970s.

Under these circumstances, where art, technology and finance meet, there is a good chance that fractional ownership companies could continue to evolve and open the borders of different disciplines to win-win propositions for all its participants. In the meantime, several questions are still in the air: will the young and established collectors continue to invest in the artworks instead of buying them physically? Will the regulation by government agencies support the art fund companies or hinder them? In an environment of rising interest rates, rising energy prices, and inflationary times, can the funds’ strategies overcome these challenges? Perhaps, if past business mistakes did not repeat themselves, we might be able to see these companies grow further and establish themselves at the forefront of art as an asset class.

Bibliography:

“The Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report 2023: Global Art Market Demonstrates Resilience.” global. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20230404-art-basel.html.

“Art Market Research & Analysis for the Art World.” ArtTactic, November 12, 2020. https://arttactic.com/.

Chen, James. “How a Closed-End Fund Works and Differs from an Open-End Fund.” Investopedia. Investopedia, January 25, 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/closed-endinvestment.asp.

“Harem: Unveiling the Mystery of Orientalist Art.” Home. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://flaglermuseum.us/harem-unveiling-the-mystery-of-orientalist-art.

“Index Funds.” Index Funds | Investor.gov. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/investment-products/mutual-funds-and-exchange-traded-4.

“Las Meninas.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Las-meninas.

“No One Did More for the Small Investor than Jack Bogle.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/01/26/no-one-did-more-for-the-small-investor-than-jack-bogle.

Society, Bocconi Students Fintech. “Art and Fintech: Fractional Investment.” Medium. Medium, February 18, 2021. https://bsfs.medium.com/art-and-fintech-fractional-investment-87a6199e897c.

Stevenson, David. “How to Own a Fraction of a Warhol.” Subscribe to read | Financial Times. Financial Times, August 11, 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/77790ee0-ce9e-4f77-995b-76e7e4f92ca2.

“Survivorship Bias.” The Decision Lab. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/survivorship-bias.

Tate. “Salon.” Tate. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/s/salon.

Tate. “'The Last Day in the Old Home', Robert Braithwaite Martineau, 1862.” Tate, January 1, 1862. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/martineau-the-last-day-in-the-old-home-n01500.

Cenk Üsel

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED