The Crying of Lot 109: An Inquiry Into Recent Auction Performance of Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild Series

Evening of 12 October 2023, London. Frieze week. Sotheby’s highlight for their Contemporary Evening Auction is a piece from Gerhard Richter’s signature Abstraktes Bild series. Known in this context as, Lot 109, it is a bold, dashing abstract picture exhibiting Richter’s emblematic squeegee work, and is estimated to sell between 16 and 24 million pounds. The work is marketed as one of the evening’s key lots, going on sale during what is possibly the year’s most significant week in art.

Oliver Barker starts the bidding for lot 109 at 11 million. Bids slowly increase towards 14,5 million, then stall for a few minutes. Noticing no more bidding for this lot, Mr. Barker claims the work has “passed”, slams the gavel, then goes on with the auction, as if nothing happened.

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild, 1986. Bought in on 12 October 2023 at Sotheby’s. Photo Courtesy: Sotheby’s.

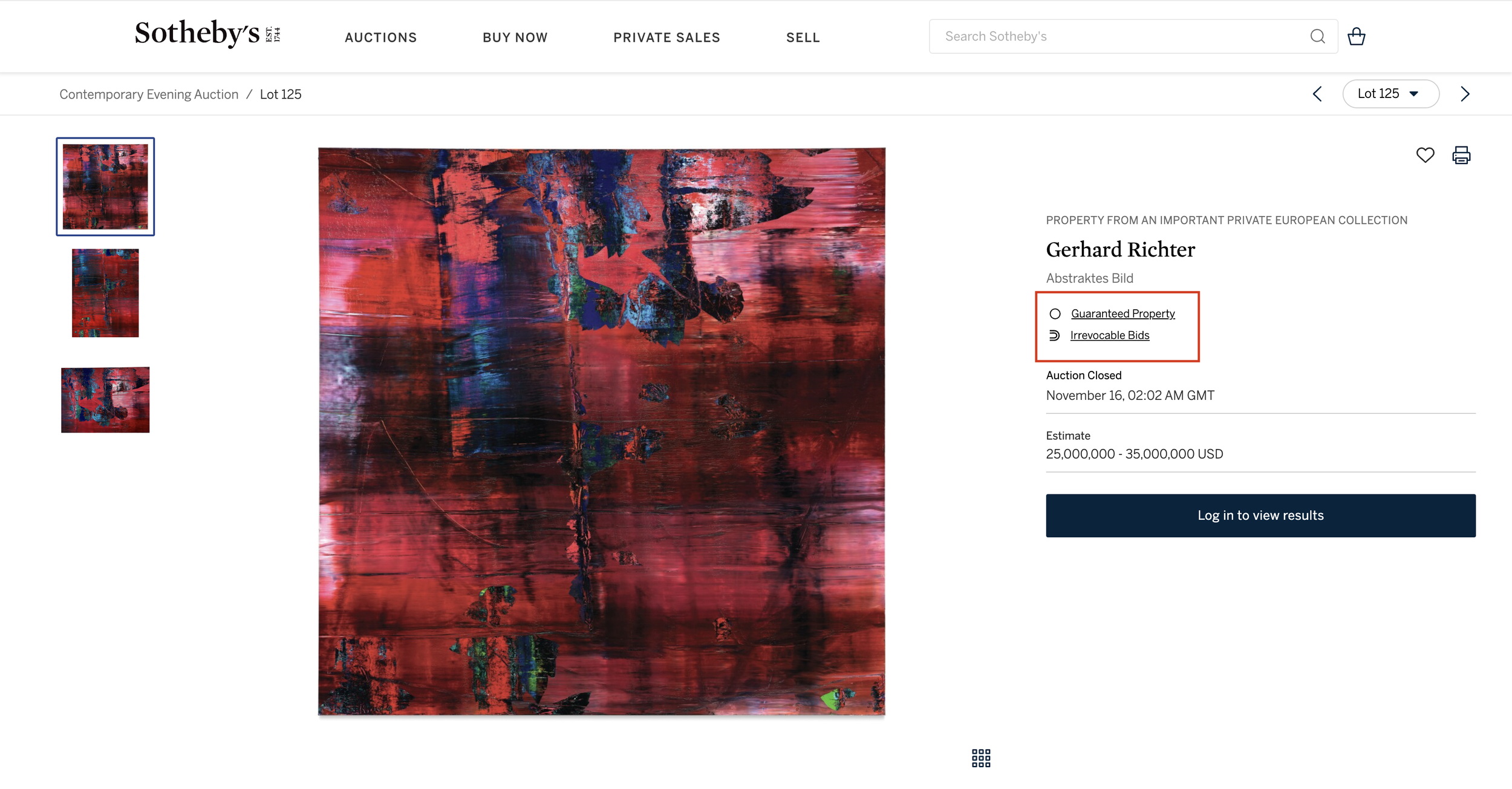

Fast-forward one month to 15 November, New York. Another Gerhard Richter Abstraktes Bild goes on sale in another Contemporary Evening Auction. This “New York” Abstraktes Bild is expected to bring in a noticeably larger sum: between 25 and 35 million dollars. Lot 125 is, much like the London lot 109, heavily marketed as a hallmark of Richter’s oeuvre, exhibiting similar techniques, only in a different color scheme – a dark burgundy instead of lot 109’s predominant, bright red. Oliver Barker starts the bidding at 23 million, then proceeds through bids increasing up to a mid-estimate 27,5 million, at which point he slams his gavel. This time, however, the painting is sold, with Contemporary Chairman Gregoire Billault congratulating the new, happy customer by telephone.

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild, 1997. Sold for 31,932, 000 USD. Photo Courtesy: Sotheby’s

These two Contemporary sales present a most peculiar contrast. We see two works by the same artist, marketed in very similar ways, and exhibiting multiple aesthetic commonalities, which nevertheless present opposite sale outcomes during the auction. Let us now attempt to elucidate this surprising discrepancy.

Claim A: The New York Abstraktes Bild is “better” than the London Abstraktes Bild.

Since the two works belong to the same visual medium, one preliminary explanation may claim that aesthetic quality is the determining factor behind the difference in sales performance. That is, the New York Abstraktes Bild is presumed to be aesthetically more complex, engaging, or simply “better” than the one auctioned in London, which may explain why it delivered a favourable outcome during the auction.

However, this claim lends itself to a number of immediate problems: in the Introduction (and, most importantly, in Sotheby’s respective catalogue essays preceding the individual sales), we saw that the same squeegee and brush techniques were used in both pieces’ creation, so there can be no possible difference in, say, technical mastery. True, the predominant colors of the paintings do differ, but it is hard to believe that such a difference may yield such a strong contrast in sales outcome.

Moreover, if colour really did drive auction sales, then all painters working today should not only stock up on burgundy but also on yellow and blue since the latter is at the heart of the Abstraktes Bild, which sold for a record 30.3 million pounds, in London, February 2015, also at Sotheby’s.

Gerhard Richter, Abstraktes Bild, 1986. Sold for the auction record of 30,389,000 pounds. Photo Courtesy: Sotheby’s.

Claim B: The New York Abstraktes Bild’s sale came at a better time than the London Abstraktes Bild's.

Global geo-political developments are widely acknowledged to have an impact on the art market, and recent events in both Eastern Europe and the Middle East are frequently cited by journalists or statisticians as influencing overall sales performance. [1] In the same vein, one can speculate that “calmer” geo-political seas may have allowed for record prices for the 2015 Abstraktes Bild, whereas the aforementioned conflicts may negatively impact similar sales in 2023.

However, it is highly unlikely that global developments may have “favoured” the New York Abstraktes Bild over the London one since the situation in both the Middle East and Eastern Europe has been largely continuous from October through to November when the two individual sales happened. As such, it is hard to believe that the wider geo-political atmosphere has favoured the New York Contemporary sale over the London one.

Claim C: The New York Abstraktes Bild was better marketed than the London Abstraktes Bild.

All auction houses place substantial emphasis on the way in which their lots are presented, either online or offline, before a sale. Comparing the individual lot webpages for the two works in question, one sees that the “winning” lot had an explanatory video attached to its page, which portrays the piece as one of Richter’s finest works and, conversely, a significant moment within the wider history of twentieth century art. [2] However, it is highly unlikely that a simple video may have attracted such a potent traction during the auction itself. Moreover, both pages present similar rhetoric regarding provenance, academic analysis, and overall sales presentation.

One plausible marketing difference between the two lots is the branding power of the New York sale being referred to as the year’s “marquee” sales. With that said, London and New York are still comparable in terms of significance on the global art market, therefore lots sold in New York are unlikely to sell de facto better than their London counterparts.

Pausing the present speculative dialectic through possible explanations regarding why the New York Richter sold, and the London one didn’t, we see that Claims A, B, and C have thus far focused on predominantly non-financial areas of the entire auction process. In other words, this article has inquired into facets of the art world which are, one might say, more “open” and “accessible” to the public and less concerned with the often shunned monetary workings of the market.

One might wonder, then, why such a dialectic has led us nowhere: can aesthetics, marketing, or geo-politics truly determine the outcome of such a sale? In the following and final part of this article, we will consider an alternative, more financial explanation for the difference in sales performance of the two Richter pieces.

Claim D: The New York Abstraktes Bild was guaranteed by Sotheby’s, whereas the London Abstraktes Bild was not.

This article’s only attempted contention for the difference in sales performance of the two Abstraktes Bild works is the fact that the New York piece was guaranteed prior to it going up on the auction podium. Before any further speculation, however, let us briefly address the mechanics of auction guarantees, and how they can influence a work’s sale.

Sotheby’s Sales Page for Gerhard Richter’s, Abstraktes Bild, lot 125, Contemporary Evening Auction, November 2023. Highlight of Guarantee and Irrevocable Bid disclosure added. Photo Courtesy: Sotheby’s.

According to Cifuentes and Ventura, auction guarantees are a type of arrangement through which auction houses attempt to grant the consigner assurance that their work will sell in an upcoming auction. [3] In other words, guarantees help auction houses secure their lots’ sales while also increasing consigner confidence to collaborate further with the said auction house.

The same authors explain that one of the principal ways in which auction houses guarantee works is through reserve prices.[4] The latter are certain contractual agreements through which the vendor – or the consigner – requests that their work does not sell until it reaches a certain minimum price or that the winning bid must pass a certain agreed threshold. Nonetheless, auction houses can also agree to sell the work even if the winning bid is below the reserve price, in which case the former pays the difference to the consigner. Depending on the guaranteeing contract, the auction house can also charge the seller a certain fee should the given work sell for a price above the initial guarantee. Therefore, we see that guarantees involve a type of risk management since they can inculcate multiple risks – and afferent profits – for either the consigner or the auction house.

Cifuentes and Ventura also highlight that guarantees have significantly risen in popularity in the past decade: in 2009, nearly none of the top auction lots were guaranteed, whereas today, approximately 40% of lots sold during the New York or London auctions are guaranteed.[5] Whether one finds these developments healthy for the art market or not [6], it is almost certain that guarantees will increasingly take up a larger portion of the discourse around auction houses and the contemporary market in general.

To return to our inquiry into the different Abstraktes Bild works that recently went on sale at Sotheby’s, one can only speculate with regards to the exact type of guarantee at work behind the New York Richter. That is, at what (reserve) price did the said guaranteed agreement specify that the work must “sell” in order for it to truly leave the vendor’s hands? Even more: could the bidding battle during the sale have been carried between the guarantor and an unexpected desiring customer, seeking, as it were, to “steal away” the Richter from the respective guarantor? In any regard, it is easy to see why Sotheby’s guaranteed the New York Abstraktes Bild went in favour of the latter’s sale – it quite literally “guaranteed” that it would sell.

Guaranteeing the New York lot may have also had numerous other effects on the sale itself. For example, bidders, seeing that their desired lot is almost certain to be leaving the auction for someone else’s wall, may be driven to bid more “intensely” in the actual sale, in a type of art market-“fear of missing out”.

The work also has an “irrevocable bid” (attached to it may have also heightened the excitement in the auction room on the evening of 15 November since the former are also increasingly utilized in contemporary auctions, much to the increase in overall speculation within the auction scene.[7] Again, one can even imagine that the “bidding war” which took place on the respective evening may have been carried out between a possible bidder – who placed that irrevocable bid prior to the sale – and the work’s guarantor themselves.

Taking a step back, however, we notice that even though the New York Abstraktes Bild’s sale was most likely “guaranteed” to happen, this still does not explain why the London Abstraktes Bild was not also itself guaranteed. Put another way, although our inquiry – or, rather, wild speculation – into the intricacies of the New York Richter’s being guaranteed to a third party has led us to believe that such financial risk management was likely responsible for the piece’s ultimate success at the Contemporary Evening auction, we still do not have a plausible explanation for why Sotheby’s has not applied this process to its London Richter as well.

And when we turn to ask why the London Richter was not itself guaranteed by a third party, we inevitably fall back again into a type of aesthetic/contextual comparison much akin to the views proposed in claims A, B, and C (i.e., has the New York Richter been guaranteed because someone found it more “aesthetically” powerful than the London Richter?). As such, our inquiry seems to ultimately fall into a redundant, even chimeric circularity: finding a (possibly) valid reason for the New York lot’s being sold reveals a multitude of other questions about its London counterpart, which nevertheless lead us astray.

Claim E: We may simply never know why the New York Abstraktes Bild sold, and why the London Abstraktes Bild did not.

Unless it is ulteriorly revealed how certain Richter works are guaranteed to third parties by Sotheby’s, the question we have posed at the beginning of this present article remains open. Therefore, it seems that our inquiry has virtually led us nowhere, and the initial question remains in a state of aporia. Nonetheless, I would like to end this article with two key takeaways.

First, our summary analysis of third-party guarantees helps to show that the public and private spheres of the auction world are always in constant interplay. That is, it is naïve to believe that the (public) bidding process during the evening auction is the ultimate determining factor regarding who obtains the pieces up for sale. As the previous discussion of guarantees has shown, certain (private) third-party agreements are always in the background to high-profile sales such as the October and November Contemporary auctions, and anyone looking to analyse such sales would do well to consider the role of such agreements.

The second takeaway is that, as important as they may be, taking such third-party guarantees as the ultimate determining factor behind sale performance inevitably raises a number of supplementary difficult questions, as we have seen at the end of Claim E.

In the end, volatile, unpredictable works such as any fine Abstraktes Bild may very well act as catalysts for the wider volatile, unpredictable art market of the twenty-first century. In considering such wider implications for Abstraktes Bild’s sales performance, the reader is further invited to consult Artnet and artprice, both very revealing of how many Richter works sell for exorbidant prices and how many similar works are frequently bought in by auction houses.

As such, virtually any Abstraktes Bild sale is worth following. As Greek entrepreneur and art collector Dimitris Daskalopoulos highlights — “The absolute truth: Go to the Richter exhibition and zero in on any square inch of an Abstraktes Bild. In it you will see everything you know and everything you do not know.”

Bibliography:

[1] The Art Newspaper: ‘The market has changed’: Sotheby’s scrapes together GBP 45.6m from Frieze Week double-header in London.

[2] New York Abstraktes Bild: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2023/contemporary-evening-auction-5/abstraktes-bild. London Abstraktes Bild: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2023/contemporary-evening-auction-3/abstraktes-bild

[3] Cifuentes and Ventura. The Worth of Art, 160.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 162.

[6] If the reader is interested in arguments against auction guarantees, he/she is invited to consult TAN’s following article: Anna Brady, “Guarantees: the next big art market scandal?”. The Art Newspaper, 12 November 2018.

[7] Krasnic, Nathan, Re-Thinking Risk Management of Auction House Guarantees and Third-Party Irrevocable Bids.

Virgil Munteanu

Art Markets Co-Editor, MADE IN BED