What Artnet Going Private Means for Auction Record Transparency

The world’s most-referenced auction database is about to become a private asset. Artnet, long seen as a pillar of transparency in the art market, is going private.

To many, this might seem like a routine business deal. But to those of us working in provenance research and catalogue-based documentation, it raises deeper questions about long-term access, accountability, and archival responsibility.

Artnet’s Price Database is one of the most widely used tools for consulting historical auction records. It is often billed as the most comprehensive resource of its kind, with more than 17 million recorded sales. And yet, as anyone who uses the database regularly knows, there are significant gaps. Withdrawn lots, bought-ins, known forgeries, and misattributions are frequently absent. Former employees have confirmed that Artnet complies with requests from clients and auction houses to remove or suppress certain results from public view. No explanations are given, no public record of changes is maintained.

Hans Neuendorf, founder of Artnet, and Jacob Pabst, CEO of Artnet. Photo courtesy of Artnet.

A spokesperson for Beowolff Capital has stated that in the near to medium term, Artnet will continue to operate “as usual,” with the same team, same offering, and same commitment to quality. “Artnet News is one of the most trusted sources for reporting on the art market and larger cultural zeitgeist,” they added. It’s a reassuring message—but it is not enough. With Artnet’s delisting from the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, those gaps may grow. Shareholder accountability will disappear. So will the already minimal transparency around data retention, editing, and removals. What happens to public access when the world’s most-cited auction database becomes a fully private asset?

This shift comes at a precarious moment. In my research on the future of auction catalogue collecting, I found that two leading museum libraries in the United States have seen their intake of auction catalogues decline dramatically. In 2016, one collected over 2,000 catalogues annually; by 2023, that number had dropped to under 500. Auction houses are printing fewer catalogues, often reserving them for VIP clients. Many sales, especially online-only ones, no longer have a formal catalogue at all. As auction houses transition to born-digital catalogues—often hosted on ephemeral platforms like Amazon Web Services—traditional systems of recordkeeping are breaking down. Libraries face mounting technical and legal challenges in capturing and preserving these materials.

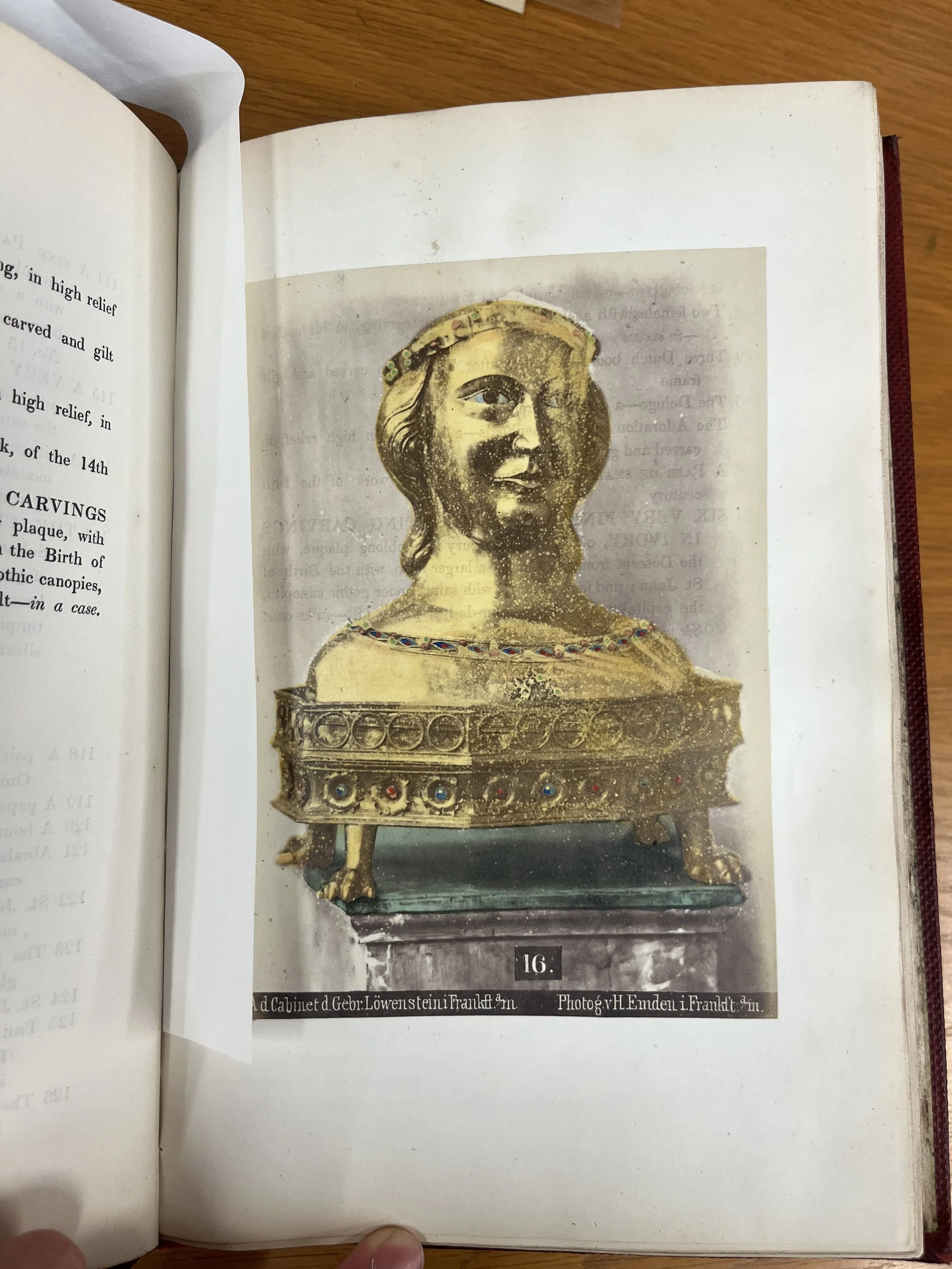

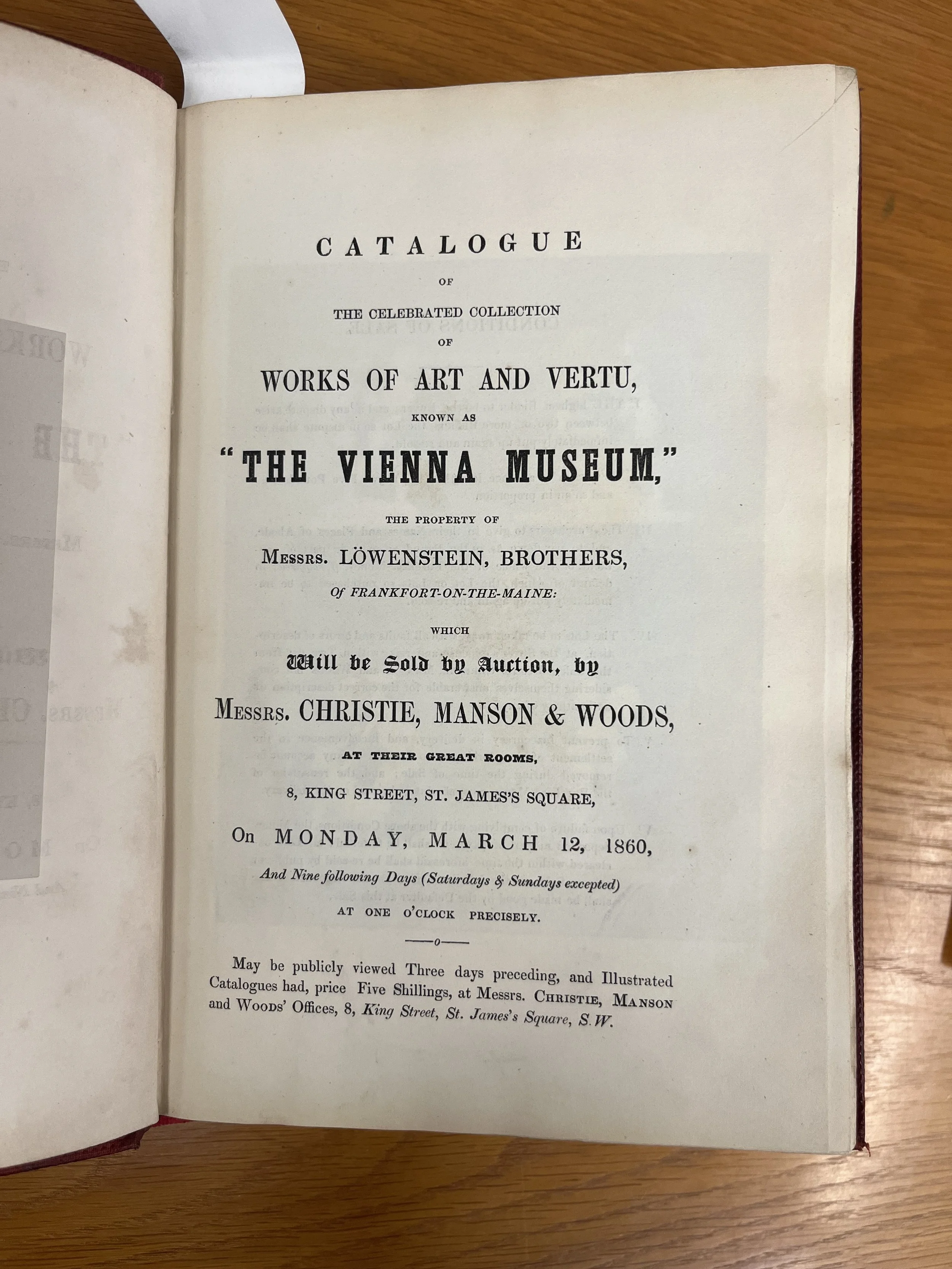

The first auction catalogue to include photographs was produced by Christie’s for the 12 March, 1860 sale of Emperor Rudolph II’s collection, famously dubbed ‘The Vienna Museum’ sale. Photo courtesy: Hector Chen.

With physical catalogues becoming increasingly scarce, researchers and appraisers often begin their investigations with third-party subscription databases like Artnet and Artprice. However, there is widespread skepticism about their completeness and reliability. The data is typically collected through automated systems that may overlook critical details, especially from smaller or less cooperative auction houses. Depth and accuracy vary significantly, and for some firms, entire sales may be missing. Even when entries are present, inconsistent standards across platforms and restrictive copyright policies often obscure the clarity and usefulness of the information. For many professionals, these databases offer only a rough starting point—helpful for identifying the time and place of a sale, but rarely sufficient. Point of the message? A physical auction catalogue is always gold, because the information online can be manipulated.

In this climate, Artnet should be the solution. Instead, it risks becoming just another walled garden—driven by profit, free from oversight, and immune to public accountability. This is not a matter of nostalgia for print catalogues. It’s about whether the information those catalogues once captured—lot descriptions, provenance chains, condition notes, and sale results—can still be retrieved, trusted, and preserved for the future. A complete chain of provenance—constructed through auction and sales records—remains one of the most reliable methods for verifying authenticity. For institutions, collectors, scholars, and appraisers, the loss of access to this information has profound consequences. If archival records become selectively edited or entirely inaccessible, the integrity of the art market itself is put at risk.

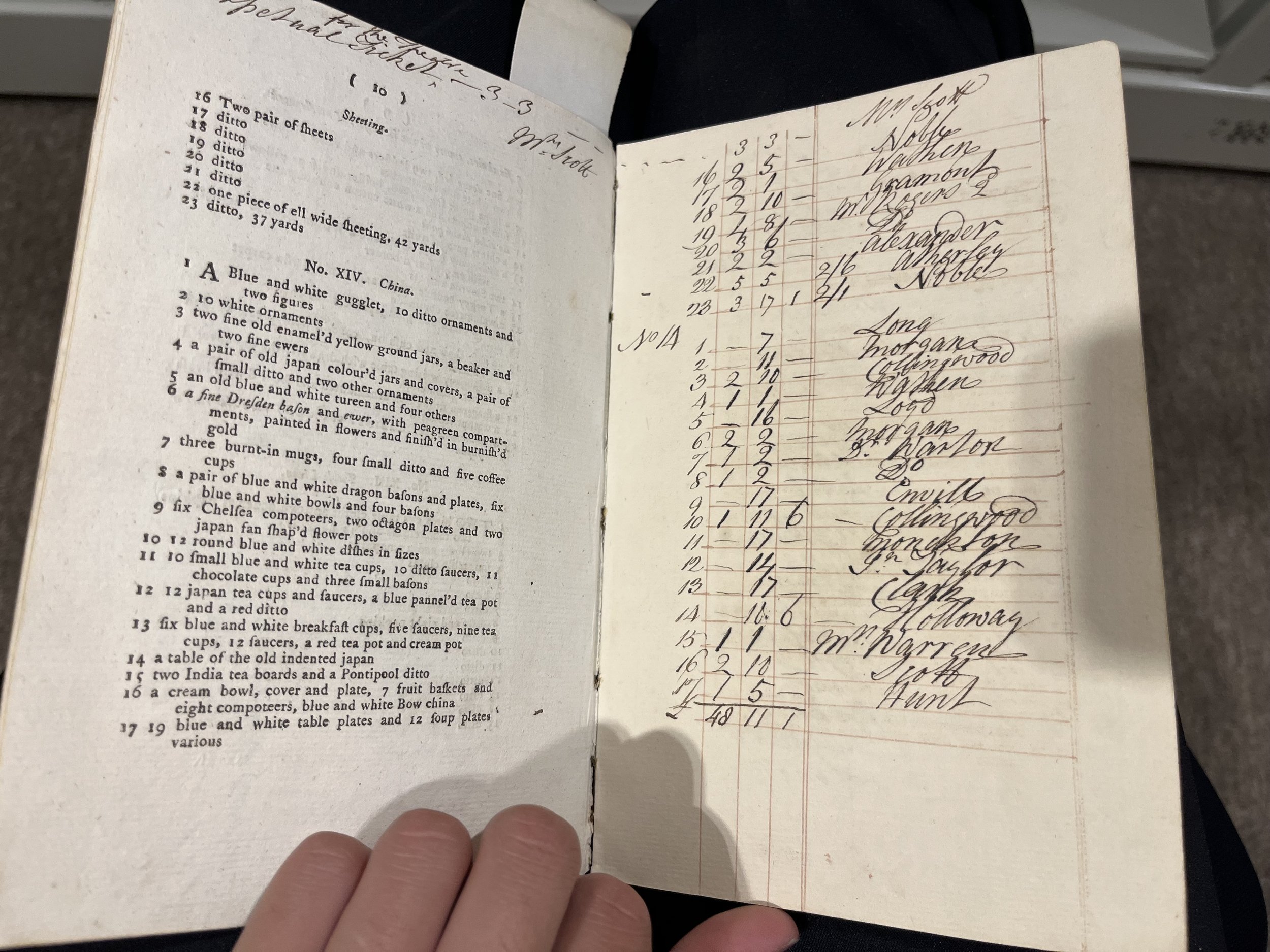

Traditionally Auction Catalogues are often included with a “price list” listing the names of the buyer. Photo courtesy: Hector Chen.

Artnet is not without competitors in this space. Artsy, Artprice, and MutualArt are all major players, with newer entrants like LiveArt and Arthur Analytics offering alternative price-tracking models and data-driven platforms. Some of these services serve different functions—Artsy focuses more on primary market listings and gallery visibility—but the core objective is the same: to track, structure, and provide access to sale records.

The real difference comes down to integrity. If, with new investment, Artnet commits to becoming a more independent, technically sound, and ethically responsible platform—by improving its data scraping tools, expanding auction coverage, and preserving records transparently—then this acquisition could mark a positive step forward.

The Artnet Price Database for Fine Art and Design and for Decorative Art remains one of the largest, most comprehensive databases for auction records. Photo courtesy: Artnet.

Without such safeguards, however, the risks are considerable. If Beowolff Capital truly envisions a "connected art ecosystem," it must understand that ecosystems require care, not just capital. Stewardship means upholding the historical record: ensuring access to past sales, refusing to quietly erase data, and actively partnering with institutions to archive digital catalogues.

The art market has long tolerated a degree of opacity, but the credibility of its history—its transactions, provenance, and attributions—depends on records that are both verifiable and accessible. That record is now more precarious than ever. To remain relevant and trusted, Artnet must rise to meet a higher standard—once trust is broken, it’s rarely regained.

Hector Chen,

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED