Up, Out & Off: Banksy’s Trajectory from the Street to the Auction House

Active since the 1990s, the elusive Banksy, whose real identity remains unconfirmed, creates street art on public spaces such as derelict building facades, bus stop shelters, and random street walls–all of which engage with the locale and beyond in the open air.

His artistic journey aims to bring the subterranean street art practice ‘up’ to the surface and literally embed it within the local community; then ‘out,’ which devises an alternate management system to challenge the notions of site-specificity and redefine the system of market distribution; and finally, taking ‘off’ from the physical realm entirely and reconstructing our notions of what graffiti has the capacity to achieve.

With the shift of his initial, literal site imagery from city walls to functional sites elsewhere on canvas and other commodifiable platforms, the artist cannily challenges prevailing systems of art pricing, popular accessibility, and the culture of gallery representation.

Banksy, Girl With a Balloon, 2002. Original mural on Waterloo Bridge in South Bank in 2004. Photo by Dominic Robinson.

In 2010, Banksy stencilled an image of a young boy holding a paint bucket onto the side of a building on Valencia Street in San Francisco, Calif., with the words ‘This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed’ scrawled around the form. The image covered one half of the side of the building, prominently positioned for easy viewing from both rooftops and at street level. Banksy’s proclamation slyly but provocatively set in motion the suggestion that an artwork which has, for now, been so casually spray-painted onto this public space, might have an even greater value. This begs the question: Should it be designated as an art object and given status within a grander institutional framework? In one swift, urban guerrilla stroke, Banksy harnesses the slippery fluidity of site-specificity and puts it to work.

Although This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed starts within the literal site, it is not reliant on that location given Banksy’s extraordinary ability to release his practice from any physical constraint. His pre-meditated choice of site for this work is judicious from the outset. The building is not only visible to the street below but sits adjacent to a neighbouring rooftop, providing an additional public theatre space where viewers can engage with the work. With a nod to those who do not have access to big-city cultural centres or intimidating stark white cube galleries, Banksy brings the art to them, questioning public access to art and redefining the very idea of a gallery space.

This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed reflects a critical moment when Banksy considered how his work, thriving thus far in a literal site, might transcend to and succeed in a functional site whilst still maintaining the street art ethos upon which it was built. That ethos was fostered within the cultural context of 1990s post-war Bristol–where Banksy is thought to be from–which was largely unbuilt following the devastation of the Second World War and the local economic decline after the once-thriving docklands were shut. Derelict buildings ripe for spraying were everywhere. Spray paint art was first embraced by graffiti artist Robert del Naja, also known as 3D, which, in turn, encouraged local graffiti pioneers Inkie, Nick Walker, and DryBreadZCrew, with whom Banksy started to work during the mid-90s. John Nation also founded Barton Hill Youth Club, a community opportunity allowing Bristol youth to graffiti legally on designated walls. However, following a surge in activity, the criminal connotations of graffiti came under attack and Operation Anderson, the UK’s largest graffiti bust, occurred in 1989 under the conservative Thatcherite government. By way of arts community pushback, however, some of the strongest and most trenchant graffiti work began to emerge just as Banksy entered the scene.

Banksy, This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed, 2010. San Francisco, CA. Image courtesy of REUTERS/Robert Galbraith.

Graffiti as a movement was first developed in New York in the late 1960s as the city suffered from extreme poverty, rising crime rates, and thriving drug culture. Young people began writing their names around town to take back ownership of their surroundings and reassert their place within the communities from which they had been marginalised. Stylistically, the imagery got bigger, and the movement spread to other neighbourhoods, and eventually to the subway system where it literally travelled throughout the city. The work came ‘Up.’

The actions of graffiti artists working in this manner (whether in New York or Bristol) were rooted in a refusal to accept the social confines in which their circumstances had put them. Graffiti was their weapon in challenging their status and pushing their horizons out beyond the limits society allowed. The work went ‘Out.’

By surfacing social, political, and economic debates in common parlance, Banksy’s language is universally understood as it assertively refuses to obfuscate nuance or the pseudo-intellectual ambiguity that can intimidate the viewer. This everyman manner comfortably brings Banksy’s purpose and messaging into the cultural conversation to be considered and engaged with regardless of the literal site. By making This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed both the work’s content and subject, he subversively alerts us to the idea that art has more value when for sale. This irony reinforces the artist’s point that the public can actually embrace works of art regardless of price tag, much less a price inaccessible to the majority of the population, but is reserved for the elite by a largely unregulated system of commerce. Crucially, the work exposes issues that are embedded in our cultural discourse and launches them beyond the wall upon which they were originally scrawled. From there, Banksy challenges the infrastructures upon which we rely and promotes their redesign. The work takes ‘Off.’

Banksy, The Mild Mild West, 1999. Bristol, UK. Image courtesy of BBC.

The Mild, Mild West offers a pivotal example whereby Bansky further expands his site. A cuddly-looking teddy bear turns to shockingly wield a Molotov cocktail back at the line of riot police that outnumbers him. Similarly to This’ll Look Nice When It’s Framed, the placement of this piece is strategically situated above a bus stop junction in the centre of Bristol which connects inhabitants from all over the city. Historically, it has been proposed that the work pays homage to the St Paul’s race riots that took place nearby in 1980. The teddy bear–a recognisable symbol of care and childlike play–represents the universal humanity of a nurturing community. The Molotov cocktail, however, suggests that the same community can strike back when provoked. Banksy subversively encourages action in the face of injustice, especially from those abusing positions of authority. The play on the word ‘mild’ instead of ‘wild’ stresses the fine line between which behaviour dominates.

As Banksy continued to explore these issues and as the work left the originating literal site, questions regarding commoditization arose which had already been faced head-on in This Will Look Nice When It’s Framed. Famously, when asked about the danger of “selling out,” Banksy shiftily replied, “I’m old fashioned in the sense that I like to eat.” A justifiable response to the dilemma of the legitimisation of owning street art and compensation for the artist’s labour.

In order to allow space for commoditisation while defending his practice, Banksy embarked on a challenge to redesign the art market, creating a trade environment that would protect the authenticity of his movement but also encourage its development. This redesign, championed by Banksy and his contemporaries, would involve manageable prices rendered for the market, a rejection of existing formal gallery representation, and independent infrastructures of manufacturing and distribution.

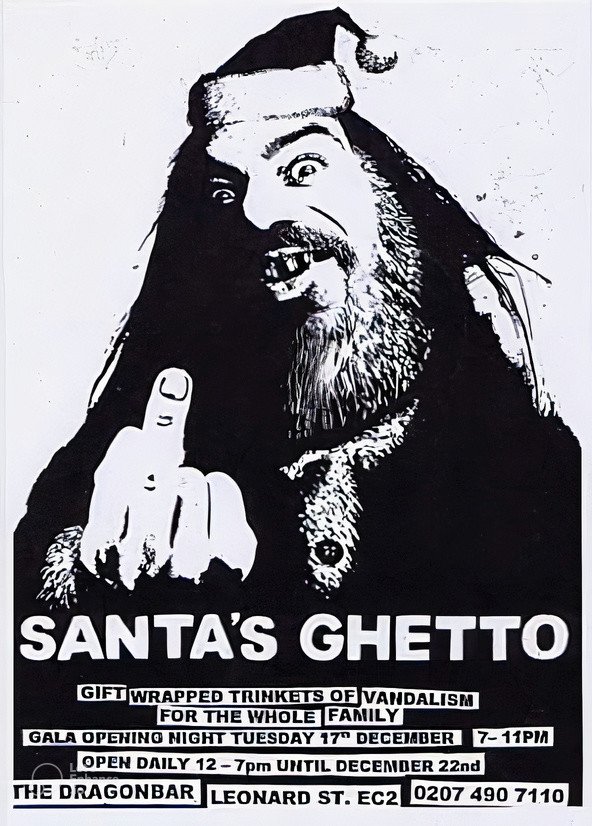

Santa’s Ghetto, a DIY gallery model and “squat art concept store” located upstairs in the Dragon Bar in Shoreditch, provided display, marketing, and sales channels for street artists outside the art world that moved beyond the wholly populist ethos of the street and graffiti art form. Further, Pest Control was designed to manage commodification and firmly root artwork within the site where it belongs. This regulatory system issues certificates of authenticity to works that have now been designated canvas-intended. This control means that Banksy can protect site-specific work and honour the intent of a piece intended for public benefit and consumption, pumping the brakes on a super-inflated art market and exerting control over his practice.

However, the conventional art world force cannot be controlled forever. Once Banksy’s work is absorbed into the secondary market, the mainstream rules apply. As a result, Banksy outrageously responded with the shredding of his 2006 painting Girl with a Balloon as the gavel struck during its sale at Sotheby’s in 2018. Speechless, the auction room crowd were forced to acknowledge the commodity fetishism that rules their art market, where the exchange of the auction house system’s financially attributed value trumps any other cultural value associated with the art. The meaning of what was left of the shredded work changed entirely, even as far as to take on a new title. Love is in the Bin has become entirely about what the artwork represents and ultimately undermines the system we use to define it, heavily critical of the institution and ultimately rewriting the discourse.

As one of the most revered street artists of the 21st century, Banksy’s imagery ultimately transcends from the literal to the functional site and navigates the prevailing systems of the art institution by moving up, pushing out and taking off. In shredding Girl with a Balloon, Banksy has made the ultimate attempt to destabilise a system of trade by actually destroying his own work. The subsequent resale of Love is in the Bin in October 2021, for nearly twenty times its price in 2018, ridicules the problematic infrastructure of the art market and demands that it be drastically reconsidered. In a world where art has been increasingly commercialised to reach new audiences, Banksy’s artistic trajectory brings the original intent of street art to the forefront from the underground into the open air and examines the considerations of its commodification.

Banksy, Love is in the Bin, 2018. Aerosol paint, acrylic paint, canvas, cardboard, 101 cm x 78 cm x 18 cm. Image courtesy of Sky News.

Sources:

Badshah, “Banksy sets auction record with £18.5m sale of shredded painting”, 2021.

Banksy and the Rise of Outlaw Art. Directed by Elio Espana. London: Vision Films, 2020.

Ellsworth-Jones, Banksy: The Man Behind the Wall, 2021, 23-37.

Marx, Karl, Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter One, Section 4: The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof.

Meyer, “The Functional Site; or, The Transformation of Site Specificity”, 23-37.

Kate Fensterstock

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED