Boss Women of the Art World: Wendy Red Star

Wendy Red Star is a Native American contemporary artist employing diverse forms of media to explore community and heritage, anti-ethnography, anti-colonialist feminism, and American romanticism. She exposes the detrimental reality of manifest destiny on her own path to self-actualisation.

Red star was born in Billings, Montana, in the United States where she grew up on the Apsáalooke (Crow) Reservation. She attended UCLA for sculpture and was becoming known as a photographer in California in 2006. Missing her community during this time, she went to a museum for the comfort of finding her heritage and history. However, what was on display didn’t resonate kindly:

“I went to the natural history museum, and I came through the dinosaur exhibitions on my way into the Native American galleries, and I just got the feeling that they were saying we were part of the past.”

Red Star’s work addresses what the United States has wilfully forgotten: that the very foundation of the nation, its government and culture, is upon the eradication and disenfranchisement of Native communities. Through photography, mixed media, and installations, she challenges the colonial values which trickle into contemporary American discourse and imagery. When she realised that her school in Montana was on Crow territory, she erected tepees across the campus. Originally with no political intent, the artist realised that the tepees became inherently political because of their anti-colonialist symbolism by virtue of existence. “As a brown person,” she states, “As a brown artist, your work is political. Whether you like it or not” (Aperture).

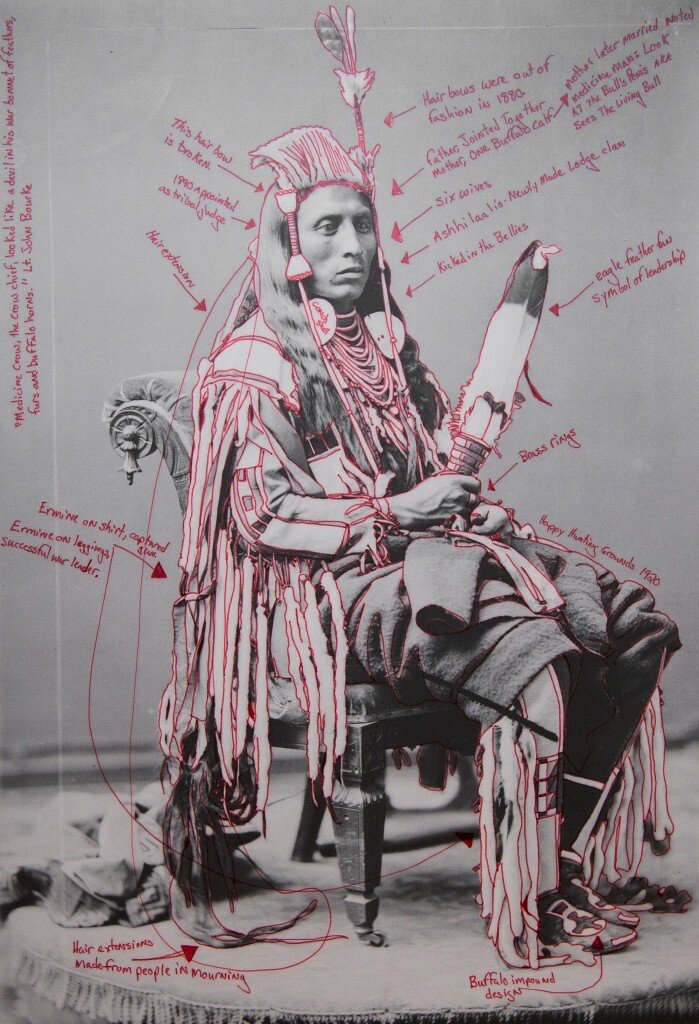

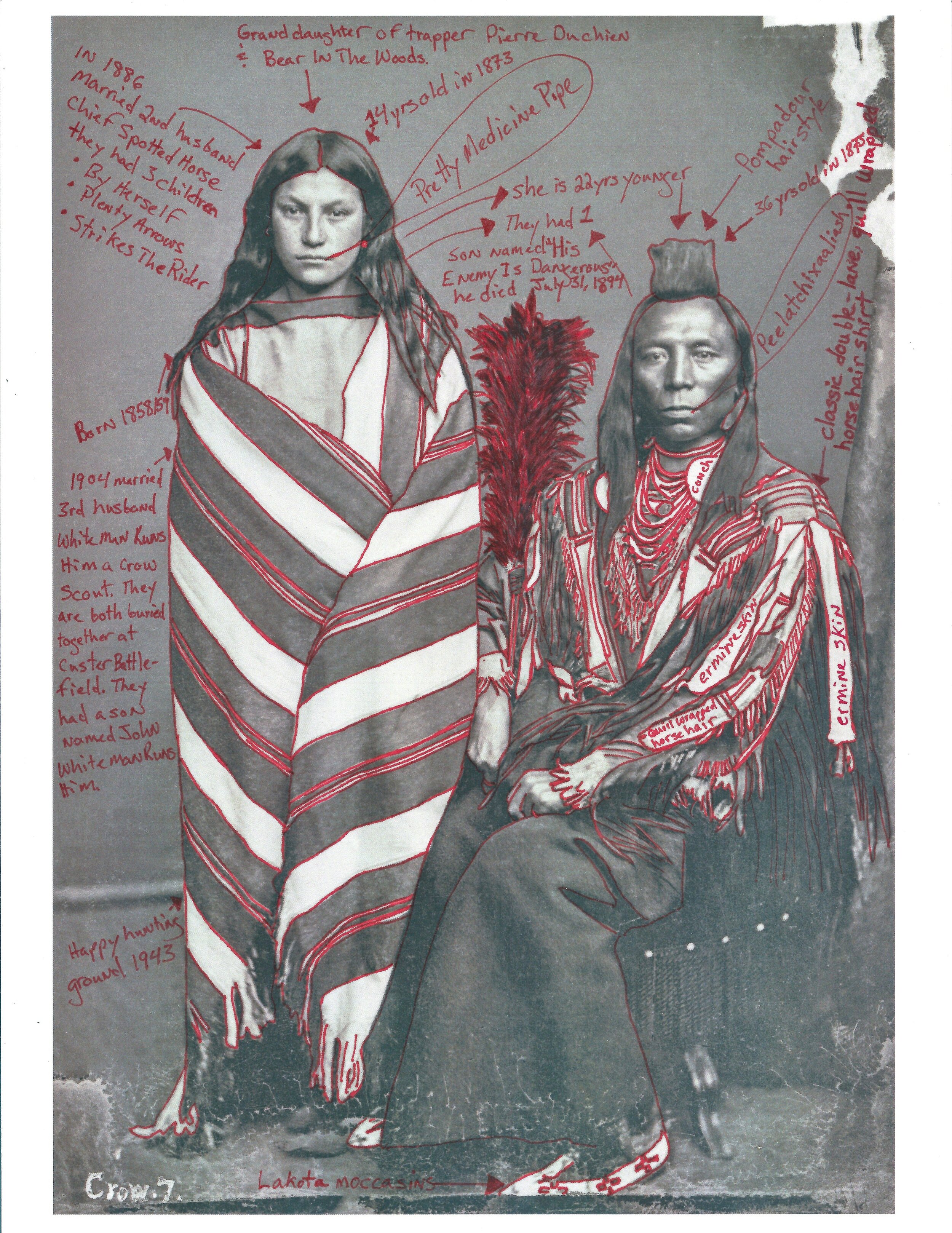

In her Peace Delegation series, early American ethnographic photography becomes a palimpsest for regaining and highlighting important cultural symbolism. The forced assimilation of Native populations in America by colonisers left both tangible and intangible heritage to suffer extensive losses. In contrast, the ethnographic photography of this same time period highlights Native American’s status as “other” in a long tradition of colonisers exoticising and disenfranchising Native cultures. By marking on the photographs forcibly taken of Native people via an ethnocentric white lens, Red Star reclaims the relationships, symbolism, and complexity of Native heritage.

The empowering survey of her artistic career in 2019, “A Scratch on the Earth,” from the Apsáalooke (Crow) word annúkaxua, invokes the ‘scratches’ impressed upon the land by the United States government when delegating Reservation land. Her work explores the relationship between the coloniser and the original inhabitants and the lasting impacts of systemic silencing.

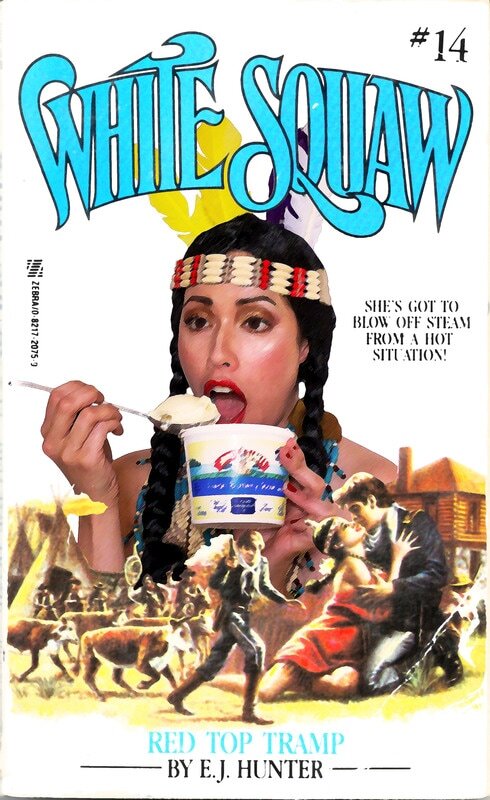

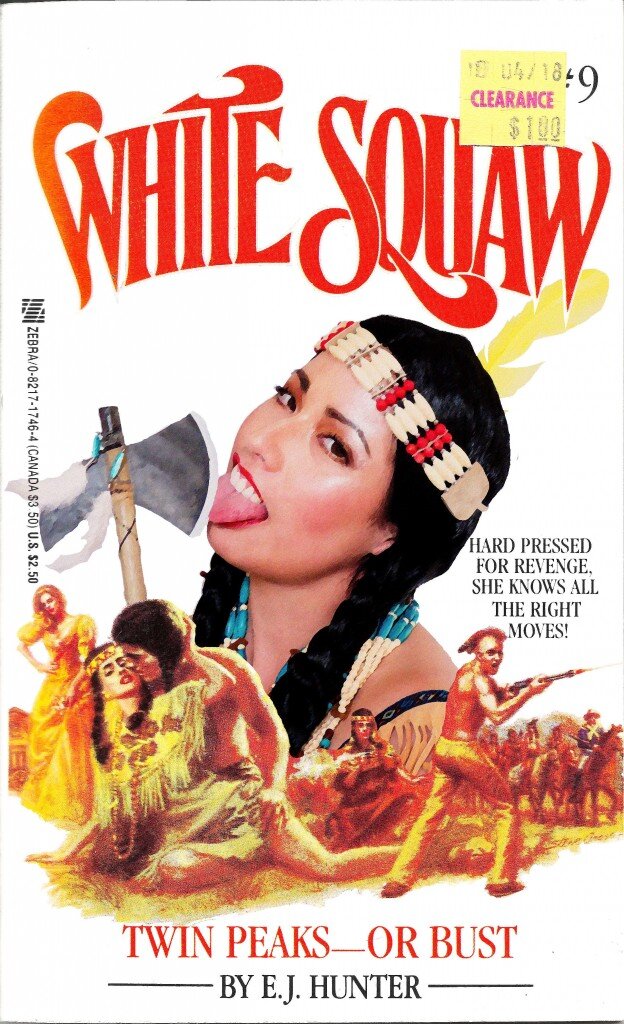

Red Star’s work approaches the double-edged sword of racism and romanticism with a sense of dark humour as well. Capitalising on the ubiquity of pulp American Frontier paperbacks, she alters covers to include her likeness. The White Squaw archival print series sees Red Star on the cover of Twin Peaks - Or Bust #9 licking a tomahawk adjacent to the sensational subtitle “hard pressed for revenge, she knows all the right moves!” and on Red Top Tramp #14 spooning Land O’ Lakes butter along with the line “she’s got to blow off steam from a hot situation!” The images challenge Native American women’s representation with biting irony.

“Humour is healing to me. Like you mentioned with laughing at funerals, everybody is so sad at that moment, to have a little bit of laughter is healing. To have that element in my work is quite Native, or Crow, and I’m glad that it comes through. It’s universal. People can connect with the work that way. Then they can be open to talking about race.”

With the exception of Red Star’s humorous appearances, the covers are formulaic in composition: a gunman on one side, lovers on the other (always with a damsel-like Native American woman). Rough riders and demolition fill the background. Contrasting against the drama of these covers is the occasional sticker denoting the price at an affordable clearance of one dollar. These prints speak to the way Americans have historically and systemically placed prescriptive narratives on Native communities and the value to which they ascribe their stories while simultaneously profiting off them. The covers from the series are from the 80’s and 90’s which feels recent, but the derogatory word squaw is still present, and the cover art appeals to a romanticised, false idea of the frontier. As Red Star explained in an interview with Venison Magazine, inserting herself into the cover imagery was taking agency of her representation.

Similarly, Red Star explores romanticised depictions of Native Americans through her Four Seasons series. Thin creases in recently unfurled scenic backdrops set a technicolour stage for cardboard cut-outs, glossy fake flowers, blow up animals, and Red Star herself seated on manicured AstroTurf. The artifice is present. The artist, dressed in traditional Apsáalooke clothing, gazes directly at the camera. The images are reminiscent of common commercial imagery depicting Native Americans. Within the setting, she is the only reality.

Wendy Red Star has recently participated with her daughter Beatrice in the creation of many artworks that engage with anti-colonial feminism including the Apsáalooke Feminist series in which Red Star and her daughter pose together on a couch dressed in traditional Apsáalooke clothing. The inclusion of her daughter, the representation and dynamic of that relationship, instils the importance of the next generation. Wendy and Beatrice have also lead tours through museums together, have undergone residencies together, and Beatrice is a forward-thinking boss artist in her own right:

“When we were there, we were figuring out things that we could do, like Wendy made a [photographic] backdrop. I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do. There were all these people giving tours, but they were all adults giving tours to kids. So I decided that I’d lead my own tour because I was 9, and that can be considered a kid. I did two on the Native floor and one on the Western. And it was like a regular tour. I went around, showing kids the artefacts, told them what they were, but I picked out my own artefacts and did my own research like a cool person would.”

A trip home in 2018 saw Wendy Red Star titled Baaeétitchish, ‘one who is talented,’ by her community. The name was originally that of her grand uncle, cultural keeper, Clive Francis Dust, Sr. Wendy Red Star asserts that, when decolonizing museum spaces, contemporary artists must be included in those conversations. Red Star encourages the mass reconciling and regathering of Native communities and especially the participation of Native women artists.

“By carving out space in the contemporary art world,” says Red Star, “I hope it will make it easier for the next generation of Native women artists to gain access to institutions and opportunities.”

Further Reading:

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/wendy-red-star-62675/

https://www.vogue.com/article/wendy-red-star-art-exhibition-a-scratch-on-the-earth-newark-museum

http://www.venisonmagazine.com/wendy-red-star.html

https://craftcouncil.org/post/qa-wendy-red-star-and-beatrice-red-star-fletcher

https://aperture.org/blog/wendy-red-star/

https://www.lightwork.org/archive/wendy-red-star/

Veda Lane,

Head of Features, MADE IN BED