When Gallery Meets Gallery: Tristan Hoare + Parafin = Alison Watt

From Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sotheby’s and Skepta, to Hauser & Wirth and Hospital Rooms, collaborations within the art world are familiar territories. Yet, to see two commercial galleries joining forces is rare. The recent alliance between Tristan Hoare and Parafin proves why more should. Together, the two West London galleries teamed up to realise a new exhibition of work by the Scottish painter Alison Watt.

Alison Watt in her studio in Edinburgh. Photo by John McKenzie. Courtesy of Tristan Hoare.

Entitled A Kind of Longing, this exhibition of new paintings is a continuation of Watt’s ongoing visual and philosophical interest in the works of Allan Ramsay, which began with an exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2021.

Although Parafin are Watt’s official gallery representatives, it was decided that the exhibition would be held in Tristan Hoare’s Grade 1 listed Georgian townhouse space in the centre of Fitzroy Square rather than at Parafin, a mere twenty minutes walk away on Woodstock Street. This decision was not made by the desire for a change of scene. Instead, it was fuelled by the friendship between Allan and the square’s designer Robert Adam. Such a happy coincidence must be fate, right?

Installation view. Courtesy Tristan Hoare.

Looking at the pictures themselves, to an unknowing visitor, they appear to be individual hyper-realistic painted objects positioned against an unidentifiable backdrop. But, even then, the subjects - a ram’s head, a rose, a silk bow, and square lace handkerchiefs, to name but a few - seem too random, too unrelated to be painted renditions of things found around Watt’s studio. And correct this observation would turn out to be.

In fact, they are not objects owned by Watts at all. Instead, they are a compendium of still-life details found in the portraits, drawings and sketchbooks held by the National Galleries of Scotland. Having been given special access to this extensive Ramsay archive, Watts was able to study these individual elements for hours on end, etching their colours, forms and textures into her imagination. Only after hours of observation does Watt retreat to the studio and let the past enter the present.

Alison Watt, Plain, 2021. Oil on canvas 78 x 78 cm/ Photo: John McKenzie. Courtesy Tristan Hoare.

What is most exciting about this series of paintings is how Watt brilliantly picks up on Ramsay’s unique ability to imbue intimacy and the essence of individual character into his paintings, drawings and sketches. One striking example is Plain (2021) which depicts a singular white rose against a taupe-coloured backdrop. For Watt, roses are particularly significant. To her, they are like people: the head of petals has folds and shadows and rich yet subtle tonal variations that all bear a resemblance to one’s own face.

More importantly, they were prominent in many of Ramsay’s sketches and portraits of women, to which Watt is especially drawn. Ramsay’s painting of his second wife, Margaret Lindsay of Evelick (c.1758-60), is a particular favourite of Watt’s and provides the source material for her painting. This tender and informal picture beautifully captures Margaret’s delicate features, which are picked up by the soft light that falls on her face. Dressed in fine purple silks laid with lace and holding one of the pastel pink flowers she was arranging, she is the humanised rose, the epitome of grace. With this in mind, one cannot help but compare the humanness of Plain with this portrayal of Margaret. Thus, Watt’s paintings appear to be neither still lifes nor portraits but somewhere in between. Ramsay’s sketch A Lady’s Left Hand Holding a Rose. Study for Margaret Lindsay Evelick (c.1758-60) provides further proof of the striking resemblance between these two paintings.

Hands were also an important subject within Ramsay’s sketching practice. Similarly titled to A Lady’s Left Hand Holding a Rose. Study for Margaret Lindsay Evelick, these sketches often denoted one particular hand holding an object, often a feather writing quill. However, rather than literally representing the feather, he would indicate its presence with a quick flick of the pen. Drawing from this, Watt entitled one of her feather pictures Right Hand (2021), as if to fill in the near-blanks from Ramsay’s sketches, conveying her innovative practice.

Alison Watt, Right Hand, 2021. Oil on canvas, 54 x 67 cm. Courtesy Alison Watt Instagram.

Such pictures contribute to the gallery’s overall calming impression. However, several unusual features stand out: two anomalously coloured subjects and inconsistent shadows.

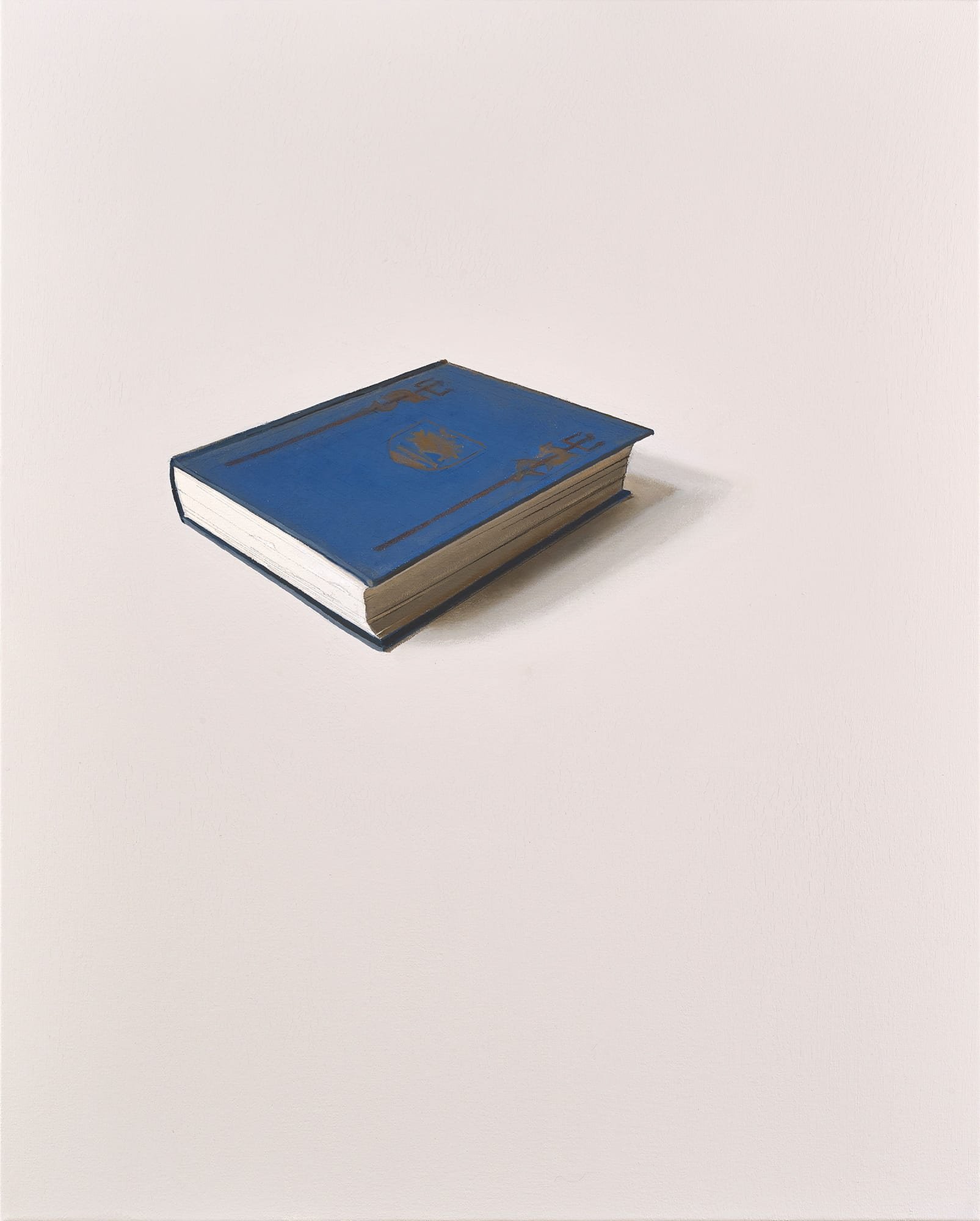

Amidst the sea of neutral pastels and muted tones, deep turquoise blue and bright garden green are easy to pick out. Found in Fox (2019) and Frances (2022), respectively, these pops of colour add the perfect touch needed to spice up a viewer’s visual palette. The former - a hardback book adorned with gold details - is a detail lifted from his Portrait of Caroline Fox, 1st Baroness Holland (1766). However, whilst this portrait depicts two books stacked askew on the side table next to the sitter, there is no exact copy of the book, which is shown in Watt’s picture. Likewise, the cabbage references Ramsay’s Franny Boscowen (c. 1748), whose portrait features a plethora of flora sitting in her breast and cabbage and hazelnuts in her hand, gesturing towards her passion for gardening. In both cases, Watt skillfully lifted these details from their original portraits and made them her own by adding her own inconsistencies in scale, the presence of shadows and the addition or omission of other small details.

Further inconsistencies are revealed when taking a closer look at the overall exhibition picture. Here, natural light is invited in by the room’s large windows to dance upon the canvases. Yet, looking around the room, one will notice that the light from the window does not always match the depiction of light hitting the painted objects. On one wall, where Temple (2021) is hung, the 11:00 morning light creates a realistic shadow. At the opposite end of the room, the shadow second skull Memento (2021) falls towards the light. The effect is surreal. Whether intentional or not, the inconsistent angle of painted shadows and real natural light creates the sense that multiple moments in time exist simultaneously. Or perhaps the space is atemporal.

But that is precisely what Watt’s paintings do. They blend the present and the past, still life and portraits, known subjects and unknown places together rather than confronting spectators with verbatim quotations from Ramsay’s oeuvre. More specifically, they present an impressive and intimate dialogue with an artist that lived and worked nearly 200 years ago, demonstrating the continued relevance of Art History. Now, this is the kind of gallery collaboration we have all been longing for.

Alison Watt: A Kind of Longing will be on display at Tristan Hoare until 10 March 2023.

Ilaria Bevan

Editor in Chief, MADE IN BED