Runqiu Peng in Conversation with Emerging Artist Chengxuan Xie

Chengxuan Xie is an artist currently studying at the Royal College of Art, Painting, MA. With an obsession with textures and combinations of different media, Xie likes to experience the compelling effect of opposite materials put beside each other. As he “punches” the work in progress, he pays attention to the nuance of the painting “punching” him back, creating dialogues back and forth.

Painting is the conduit for Xie to experience the outer world and interact with different people before reflecting on himself. His work first records the quick responses he has to a place or a person and then is brought back to the studio to be further processed. Xie wants to break the hierarchy of artists controlling their works of art but allow the images to grow organically, encompassing traces of the environment.

Chengxuan Xie.

Before the interview, it is worth having a look at an art project that is always on Xie’s mind, and it was captured by the following poetic lines:

I want to roll out a 50-meter-long paper along the coastline.

Frottage with crayon and graphite,

shells and crab hole,

weed and waves,

setting sun,

Shadow with love.

Christmas 2022, 2022. Acrylic, graphite, crayon on synthetic paper, 40 x 106.5 cm. London, UK.

Runqiu Peng: Your use of media is quite a complex combination. Acrylic, graphite, ink, and crayon are all common materials in your work. How do you play with the medium you use?

Chengxuan Xie: I like the interactions between different materials. The synthetic paper I’m using now is specially customised in a paper factory. It is very thin but can take in whatever pigment I want to use, presenting textures and layers of different media. I like the playfulness of putting opposing materials together. For example, if you put watercolour on top of wax or crayon, it will move around on that layer, not being able to be absorbed, and this is when textures appear. You can also put acrylic on top of graphite, sealing up the graphite, and then put another layer of ink on top. These different layers create interesting reactions.

The Rush, 2023. Acrylic, graphite, ink on synthetic paper, 62 x 78 cm. London, UK.

I think when most people do their artwork, they want to shape the painting strongly with their wishes. It’s like punching the canvas until it becomes what they want. Sometimes when we punch it continuously, it will also punch us back, but we mostly ignore it. I want to react to that punch my painting gives me and continue after it shapes me, going back and forth with the image. In this sense, the painting becomes complicated, creating different layers. You can see the calls and answers between each material, collaborating and competing simultaneously. You can see the discontinuation of the graphite and crayon, communicating with each other under the same image, increasing the complexity and abundance of the work.

Picnic, 2022. Acrylic, graphite, ink, wax on synthetic paper, 137.5 x 125.5 cm. London, UK.

RP: You have your own philosophical ideas behind your painting. What do you want to achieve through those dynamic processes in your creation?

CX: There is a saying from the Hong Kong film director Jiawei Wang that says: “The meaning of artistic creation is to reflect on myself, experience the world, and interact with all different kinds of people.” However, I think the meaning of my artistic creation is first to experience the world and interact with all different kinds of people, then reflect on myself. Woman and Dog in Hyde Park is a work that records my encounter with the environment around me. I brought a paper to the riverside of Hyde Park to do the rubbing, pressing it onto lawns and tree trunks, leaving their traces on the paper. I also tried to record the spontaneous response the environment gave me. Then I brought the paper back to further work in my studio. I choose this method because I don’t want to simply draw things in front of me but also things behind me that make up the whole environment, giving a response to the space I’m staying in.

Woman and Dog in Hyde Park, 2022. Acrylic, graphite, oil pastel on synthetic paper, 70 x 134 cm. London, UK.

Another response I make is to the models I work with. I practice human body sketching every week, responding quickly to a person with my pencil in 2 to 5 minutes and recording my reactions immediately. Those encounters with the outer world and humans are the first phases of my creation. In this next phase, when I return to my studio, the unfinished paintings are detached from the circumstances they were created, away from Hyde park or the model. Now I’m solely facing myself, shaping the image with my personality, which is when I reflect on myself.

No matter what artists draw, they express their inner unconsciousness and show their characteristics. For the famous Chinese painter Baishi Qi, even though the subject he paints is just a cabbage or a shrimp, his personal traits are explicitly delivered within a few simple lines. His whole 90 years of life are incorporated into the subject he depicts.

Woman and Bird, 2022. Acrylic, ink, crayon on synthetic paper, 39 x 27 cm. London UK.

RP: You are deeply influenced by Chinese art and culture. Can you give us some names that give you the most inspiration?

CX: I started reading Xin Mu’s literary memoirs as an undergraduate. He shares his understanding of the history of world literature from his perspective, which is easy for me to understand western classics. I also like Dongpo Su’s calligraphy because it reflects his positive, light-hearted attitude. There is an anecdote about him that I like a lot. One day when his friend visited him, he was lying on the bed writing calligraphy. His friend asked him why he didn’t sit up straight and write it properly, and he replied, “everyone wants to write good calligraphies, but no one does the bad ones. I will take care of the bad ones then.” His positivity and relaxation towards life are what I aspire to.

I also like Da Zhu, Ting Yin Yung, and Daqian Zhang. I especially admire Daqian Zhang’s humble spirit. As a famous person like him, he can still abandon all the things behind and go live in the desert for two to three years to learn the Dunhuang frescoes, which I think is something that only masters do.

Mother and Son, 2022. Acrylic, graphite, crayon, ink on synthetic paper, 64 x 62.5 cm. London, UK.

RP: Besides Chinese culture, are you also influenced by Western Art History?

CX: I would say that the influence is more in the technique. Western images have an abundant history to learn from, and those art masters also benefited from the traditions. For example, Pablo Picasso imitated Ancient Greek-style paintings; Paul Cézanne adapted Nicholas Poussin’s style, who also learned from the Ancient Greeks. The things we are painting now cannot be something brand new that discards our thousands of years of history. Instead, we must have been embedded in the image inheritance our predecessors gave us. Of course, the way I interpret Western paintings is also in a Chinese mindset, but I think that’s how things work. The time we can spend on paintings during our life cannot be more than 100 years, but the historical heritage of style has developed for thousands of years. The legacy from the past cannot be ignored.

I love many Western artists. When I started sketching, Egon Schiele appealed to me very much. I’m also fond of David Hockney and Picasso. In terms of ancient art, I admire Assyrian reliefs in the British Museum and Ancient Greek vase paintings.

Duck, 2022. Acrylic, graphite on synthetic paper, 19 x 23 cm. London, UK.

RP: What role does art play in your life?

CX: I’m a Christian, and I believe God has decided the road, and I only need to follow. I started to make art just because I was on this path. Things came naturally to me. I studied visual arts in Hong Kong, was signed by a gallery and got accepted by RCA, which all happened step by step. When I graduated from Hong Kong, my family wanted me to help them run our IT company, but I asked them to give me one more year to try the art path. If I couldn’t build up my artistic career that year, I would go back and help my family out. Luckily I was discovered by a Hong Kong gallery, and here I am.

I never consider art as such a big deal. Art is just part of life, and there is so much more about life. Franz Kafka was just an employee at a bank, writing novels in the middle of the night. He even asked his friend to burn his works after his death. His life was so artistic, but art is not all of life for him. I am just so lucky to be an artist and sustain my life simultaneously.

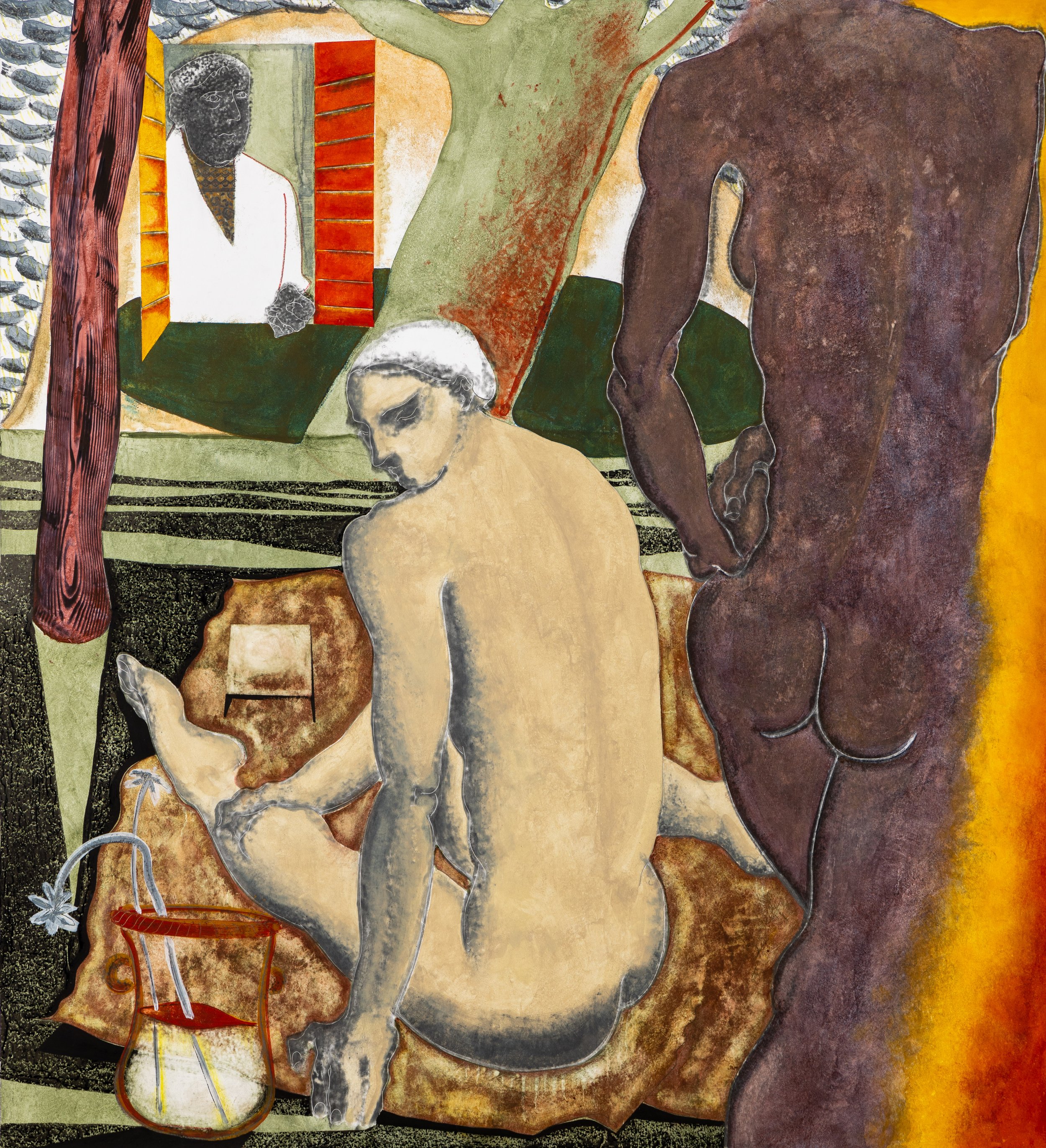

Bathing Beauty, 2023. 60 x 66 cm, Acrylic, graphite, crayon on synthetic paper. London, UK.

All images are courtesy of the artist.

The interview was conducted in Chinese and later translated into English.

Thanks to Chengxuan Xie on behalf of MADE IN BED.

To learn more about Chengxuan Xie, follow him on Instagram.

Runqiu Peng

Interviews Co-Editor, MADE IN BED