The Rossettis @ Tate Britain

“A hothouse of sensuousness and big hair” - Evening Standard

“Lurid, luscious-lipped beauties drown out the family’s real talent” - The Guardian

“Radical? Plain creepy, more like” - The Telegraph

The numerous and varied headlines summarise the gap between what was expected and what was really shown in Tate Britain’s blockbuster exhibition, The Rossettis (4 April - 24 September 2023). And the overstuffed aesthetic portraits will certainly not help to cover the disparities of this show.

The decision to confront the viewers with poetry, rather than art, at the entrance of the first room is quite an impressive opening. Indeed, the poems written by Christina Rossetti presented here reveal her premature and effective talent. The sister of the infamous Dante Gabriel Rossetti is now considered as one of the most important poets from the Victorian era. Unfortunately, her recognition is celebrated more than one century after having been overshadowed by her more publicised and controversial brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

“You took my heart in your hand

With a friendly smile,

With a critical eye you scanned,

Then set it down,

And said: It is still unripe,

Better wait awhile;

Wait while the skylarks pipe,

Till the corn grows brown.”

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828-1882), Portrait of Christina Rossetti, 1866, coloured chalk on blue-gray paper, 79 x 63.5 cm, Private collection. © Tate Britain.

Despite the unique display of Christina’s poems alongside the artwork in the exhibition, this focus was fleeting for the show excessively focused on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood co-founder, Rossetti. The aim to demonstrate the intellectual and religious character of this British family of Italian descent has not been emphasised enough. The two other siblings — author and nun Maria Francesca Rossetti and art critic William Michael Rossetti — are only mentioned briefly in an exhibition that was advertised as being dedicated to the whole family and their contemporaries.

Thus viewers were dismayed to discover that the show would be another Dante Gabriel Rossetti retrospective rather than a pioneering take on the movement. Instead, the attention was focused on his colourful, aesthetic and flowery women's portraits, with a display orienting the viewers to acknowledge the painter’s inspirations from poetry to Christianity and the Italian Renaissance.

To show a progression in the art of the British painter, the exhibition features pictures of his early years in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and charts the development chronologically. Heightening this point, it included caricatures and drawings of his fellow founders, including William Holman Hunt. The pictures, not necessarily helpful to understand the impact the Brotherhood had, are insistent on the young artists’ will to break with the former standards of the Royal Academy and become more modern by sourcing their materials from the Middle Ages whilst painting with more realism. The following rooms display varied portraits of Rossetti’s muses. The labels supporting them inform the viewer of the painter’s inspirations, especially poetry with poet Dante Alighieri from whom he adopted the name Dante as a tribute. However, this exhibition does not even succeed on this solo front due to the museum’s astonishing lack of critical position on Rossetti’s creative process.

The single dedicated rooms to Fanny Cornforth, Jane Morris (née Burden), Alexa Wilding and his long-time partner, then wife Elizabeth Siddal, fail to mention how intertwined Rossetti’s private and professional lives were. In addition, his relationship with Fanny Cornforth, his mistress before and after the death of his wife, which lasted for over two decades, is not given enough dedication.

Similarly, Rossetti’s intimate relations with Jane Morris, wife of Art and Crafts member William Morris, was not enough developed and criticised. Moreover, the institution's inability to explain these women's impact on Rossetti’s emotional but creative mindset is an understatement.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Bocca Baciata, 1859, oil paint on panel, 32.1 cm × 17 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. © Tate Britain.

The model here is Fanny Cornforth (1835-1909). She began a relationship with Rossetti soon after meeting him in 1856. She moved with him after the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, and the relationship continued until the artist’s death in 1882.

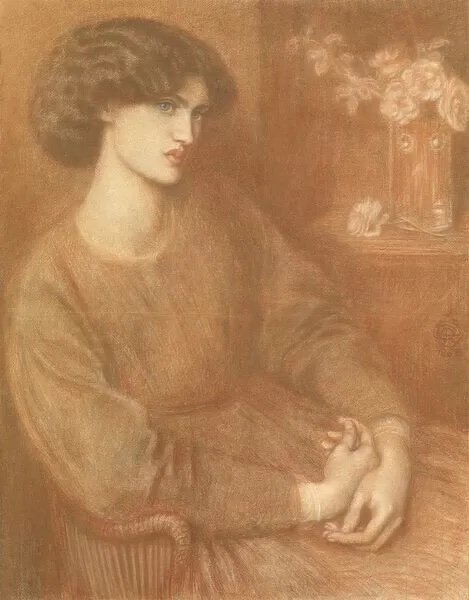

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Jane Morris, 1868, coloured chalks on paper, 88.3 x 69.2 cm, Private collection, The Maas Gallery. © Tate Britain.

18-year-old domestic worker Jane Burden (1839-1914) met Rossetti and Art and Crafts member William Morris (1834-1896) when they were painting murals based on the legends of King Arthur in the Oxford University Union. Shortly after, Jane married Morris, with whom she had two children, and eventually became Rossetti’s muse. Historians believed that she became his lover in the late 1860s, the two also living in an Oxfordshire country house mostly during the summers.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, c. 1864-1870, oil paint on canvas, 88 cm x 69 cm, Tate, London. © Tate Britain.

Another woman close to the Rossetti family, who was limited to the role of muse or wife of Dante Gabriel, is Elizabeth Siddal. The exhibition, however, presented a less than satisfactory attempt to share her works and recognise her as an artist in her own right to audiences. This was because they omitted specific details regarding her relationship with the Pre-Raphaelites and her husband. This discourse, implying that she was first a passive model and then a student who was taught how to draw and paint, contributed to idealising her husband’s impact and, most extensively, the Rossettis by presenting them as radical.

Apparently, Dante Gabriel was radical because he went against the status quo by marrying Elizabeth, a lady from a lower-middle-class background. Nonetheless, what the exhibition failed to mention is that they married in 1860, a decade after the beginning of their tumultuous romantic relationship and after Siddal was already ill, depressed and consumed by the numerous infidelities of Rossetti, suffering a probable abortion and a drug addiction to laudanum. All of this led to her tragic death in 1862 after giving birth to a stillborn child in 1861.

Behind the melancholic figure, Siddal was a profound, prolific and talented artist whose works were exhibited in a room entitled “Medieval Moderns”. The small and deeply emotional pictures contrast her husband’s dull aesthetic and the repetitive, wearying portraits of his muses-mistresses in the following rooms.

Elizabeth Siddal (British, 1829-1862), Lady Affixing Pennant to a Knight’s Spear, c. 1856, watercolour on paper, 137 × 137 mm, Tate, London. © Tate Britain.

Elizabeth Siddal, Sir Patrick Spens, 1856, watercolour on paper, 241 × 229 mm, Tate, London. © Tate Britain.

The only exciting highlight of the exhibition is found far too late at the end of the show: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s relationship to Orientalism is evoked by The Beloved. What one can say about this strange painting, whose creative process occupies an entire room, is that it creates some frustration, at least for the less sensitive.

For those who are more emotionally involved or self-aware, the lack of critical explanation from Tate Britain is a huge miss and disappointment. Presented as what is known to be the only Orientalist work of the painter, The Beloved is primarily representing black models, including Fanny Eaton (1835-1924). Given its closing position preceding the lacklustre rooms before it, this unusual subject is overlooked, which is a shame for it certainly would have otherwise caught viewers’ attention. Moreover, Tate did not sufficiently discuss and critically analyse the artwork, which did not help further to understand Dante Gabriel Rossetti's thoughts on the subject either.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Beloved, 1865-1866, oil paint on canvas, 80 cm × 76 cm, Tate, London. © Tate Britain.

The overall strangeness of the painting is summarised by Tate in the description label, where “Viewed today, the work is sometimes seen as idealising whiteness”. Furthermore, the idea that “Gabriel imagined ‘universal beauty’ as an array of racialised appearances and cultural accessories, styled as an ‘oriental’ fantasy” only heightens the dissatisfactory and simplistic attempt to educate audiences about the works. “Universal”, however, does not necessarily mean “equal”. Thus the two black models don't seem to occupy the same roles as the other characters in the scene. For instance, Fanny Eaton is almost entirely hidden in the right background, and a black child is in the foreground but depicted as a servant.

Ultimately, The Rossettis failed to answer our most anticipated questions. Who were they, really?

Radical? Certainly not. What the Tate accidentally succeeded in showing was how Rossetti preferred to draw inspiration from his private life without acknowledging the women he depicted as collaborators. Artistically, the exhibition confirmed that, whilst their paintings are superb visually, Rossetti did not grow throughout his career as he merely continued painting similar patterns on his women's portraits. One can call that monotonous. Either way, Rossetti is anything but radical, quite on the contrary.

Romantic, then? Yes, but this view only pertains to the works of Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal. They both added depth to their works, characterised by melancholia and boldness. Their romanticism is embodied by their expression of desire and womanhood.

What was supposed to be a forthcoming and exciting exhibition on one of nineteenth-century Victorian Britain's most interesting intellectual families is more of an overstuffed show on Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Counterproductive by not fulfilling its aim of allowing viewers to learn new discoveries, the exhibition is revealed to be an uncritical discourse on visual culture. It symbolised what is not expected of museums today: a need for perspective.

The Rossettis is on view at Tate Britain until September 24, 2023.

Noémie Ngako

Art Markets Co-Editor, MADE IN BED