Amy Sherald: American Sublime @ the Whitney

Amy Sherald’s 2025 retrospective, American Sublime, is a celebration of the presence and pride of everyday African Americans, realized through her contemporary portraits. It is Sherald’s first solo exhibition at The Whitney Museum of American Art, a survey she described as, “a call to remember our humanity and our insistence of being seen.”

Sherald’s forty-two portraits of African Americans were either literary-inspired, allusion-rich, culturally influenced, or history-based. Her visual discussions on politics, leisure, fantasy, gender, sexuality, women, children, and disability altogether invite a continued jubilant shift in the way Black Bodies are received.

Curated in chronological order, and hung at eye-level, her use of colour, attire, body language, lighting and context, make her centered compositions easy for viewers to connect with.

As a Georgia-born forty-four-year-old, Sherald burst onto the world’s portraiture scene in 2018, when she unveiled her most illumined portrait, Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, America’s first African American First Lady. The demand to view this six-foot-tall portrait led to hanging it alone in a spacious gallery, a luxury not afforded by any other portrait in the entire exhibition. The precision lighting directs the viewer’s eye to Sherald’s signature grey-skin-tone on Mrs Obama. Additional beams focused on the red, pink, yellow, grey and black rectangular patterns on the white dress are said to have reminded Sherald of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s geometric paintings, as well as the geometric designs of the Gees Bend Quiltmakers. Gees Bend is a region in Boykin, Alabama where former enslaved African American women initiated the practice of sewing one-of-a-kind quilts made from scraps from different fabrics.

Amy Sherald, Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, 2018. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. The National Portrait Gallery is grateful to the following lead donors for their support of the Obama portraits: Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg; Judith Kern and Kent Whealy; Tommie L. Pegues and Donald A. Capoccia. Courtesy of the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery.

However, Sherald’s rise to this Michelle-Obama-moment, and her formal academic commitment to portraiture began more than two decades ago.

After switching from Pre-Med to Art during her Junior year at Clark Atlanta University, she earned a Bachelor of Fine Art in 1997, and a Master of Fine Art in 2004 from Maryland Institute College of Art. Unfortunately, in 2004 she was diagnosed with congestive heart failure, which led to a 2012 heart transplant, a life experience that influenced her practice and perspective.

Six portraits completed during the height of Sherald’s medical crisis are included in this exhibit, one of which is Hangman. It is her earliest work on display, shared with the public for the first time, about a disquieting American truth. It is also one of two portraits where the face is presented from a side perspective, a pose that counters her traditional forward-facing, calmly gazing models. Known to incorporate uplifting colors to tell her stories, the dull purple, rust orange, and gloomy grey colors in Hangman suggest a foreboding tale. Although the portrait references a hanging, the artist stated it is a counter narrative—a reverse-lynching—because the noose is absent and the subject is alive. Most common in Southern States in America, from post-Abolition of Slavery, through the first half of the 20th century, lynchings were mob sanctioned public hangings by white Americans, against African Americans. Hangman shares a thematic racialized violence connection with the Breonna Taylor portrait. Ms Taylor was a twenty-six-year-old African American who was fatally shot by police officers, a tragedy that led to weeks of national protest. Sherald was commissioned by Vanity Fair magazine to create Taylor’s portrait for their September 2020 cover. This is Sherald’s first posthumous work.

Amy Sherald, Hangman, 2007. Collection of Sheryll Cashin and Marque Chambliss. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph by Kevin Bulluck.

Amy Sherald, Breonna Taylor, 2020. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, purchase made possible by a gift from Kate Capshaw and Steven Spielberg/ The Heartland Foundation and the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, KY, purchase made possible by a gift from the Ford Foundation. Photograph by Joseph Hyde.

“I wanted to honor her not just as a symbol of injustice, but as a woman who lived, loved and was deeply loved in return.” [1] As is Sherald’s tradition, Ms Taylor steers calmly and directly at the viewer. The fabric’s sway in this blue-green empire waist dress can be attributed to an imagined ethereal source. With her right hand placed on her hip, and left arm falling loosely and relaxed, Sherald captured Ms Taylor’s confidence and her grace.

In addition to her practice being informed by current or historic events, Sherald is an avid daily reader, a routine she views as a form of meditation and a source that feeds her artistic creativity. For instance, Listen, you a wonder. You a city of a woman. You got a geography of your own is from Lucille Clifton’s 1980 poem, “What the Mirror Says.” She describes this portrait as “a powerful affirmation of Black womanhood, self-worth and emboldened identity.” Her simple color selections of white, black, and grey, with a pale-blue background set the tone for a visual narrative that supports the title of her portrait.

Amy Sherald, Listen, you a wonder. You a city of a woman. You got a geography of your own, 2016. Collection of Rashid Johnson and Sheree Hovsepian. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph by Joseph Hyde.

Her Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), is also inspired by literature, with Lewis Carol’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Here too, a woman is dressed in sophisticated attire with accompanying props to support the title. However, this portrait sets the stage for her Michelle Obama encounter, as it won the 2016 grand prize in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery’s competition. Sherald is the first woman and first African American to win this Outwin Boochever prize. The grand prize included the opportunity to create a commissioned portrait; hence Sherald being selected to create the portrayal of Michelle Obama.

Amy Sherald, Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), 2014. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph by Joseph Hyde.

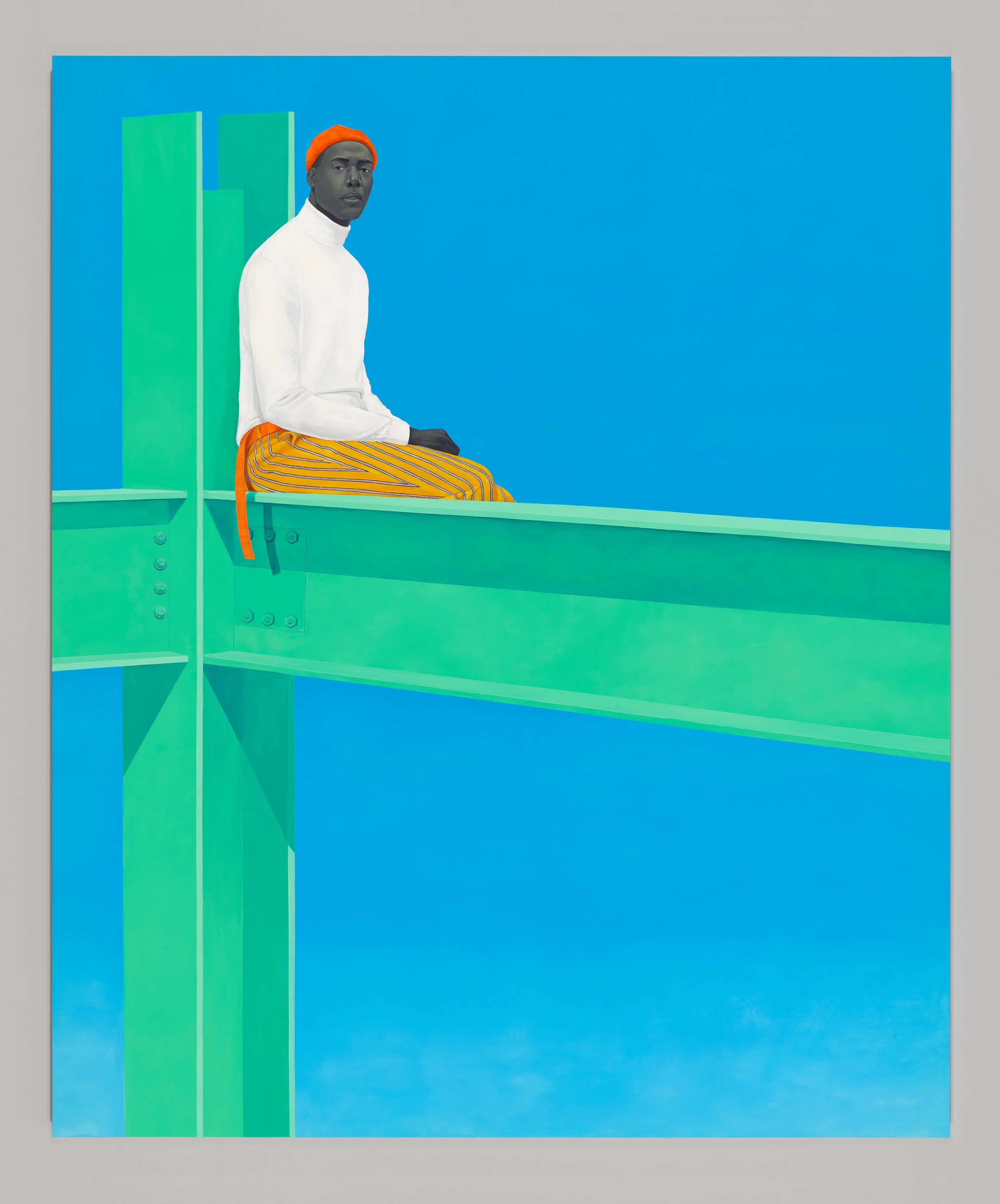

Visual American histories have also provided moments for Ms. Sherald to expand discussions that include African Americans. If You Surrendered to the Air, You Could Ride It, was inspired by Charles Clyde Ebbets 1932 photograph, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper. This iconic black-and-white photograph shows eleven ironworkers on a steel beam, who are Irish, Italian, Scandinavian, German and Native American. Sherald reinterpreted this photo by infusing color with vivid turquoise green steel beams, and a bold cerulean sky. Rather than include a group of eleven African American men to mimic the original photograph, she opted to include only one man. This singular African American man’s presence in this Building-of-the-American-Skyscraper story, makes their contribution abundantly clear.

Amy Sherald, If You Surrendered to the Air, You Could Ride It, 2019. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchased with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee, Sasch S. Bauer, Jack Cayre, Nancy Carrington Crown, Nancy Poses, Laura Rapp, and Elizabeth Redleaf 2020.148

Caption: Clyde Ebbets, Lunch Atop a Skyscraper, 1932.

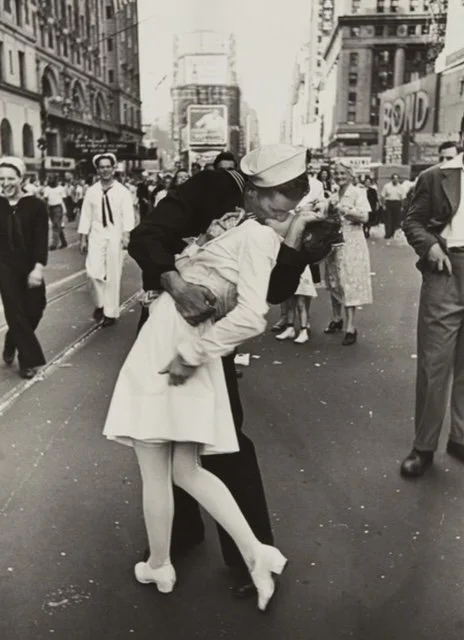

Another portrait influenced by a historic photograph is, For Love, and for Country, which references Alfred Eisenstaedt’s 1945, V-J Day in Times Square. Here, an American sailor, overjoyed by news that World War II had ended, spontaneously kissed a female stranger. Sherald was also a stranger to the two male African American models selected for this portrait. Her choice to recast the characters in this end-of-war visual was to remind, or inform, viewers of African Americans who also served in World War II. The presentation of two men embracing and kissing, alludes to renewed attacks on sexuality and gender within the military. She also revamped the photograph, by selecting red, white and blue colors in some clothing, paying homage to the American Flag. Sherald seamlessly commented on American military history, race, gender and sexuality in this single portrait.

Amy Sherald, For Love, and for Country, 2022. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Helen and Charles Schwab. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & WIrth. Photograph by Joseph Hyde.

Alfred Eisenstaeddt, V-J Day in Times Square, 1945.

Sherald’s thirteen years of Catholic schooling coupled with her expertise in art history, have informed her Mother and Child portrait. Her credentialed knowledge of art, from Antiquity to present, means she would be aware of Egypt’s Isis with Infant Horus, and Medieval and Renaissance art’s Madonna and Child. Unlike art history’s traditionally meek, well-dressed, veiled or haloed mother and child, Sherald’s twenty-first-century African American mother resembles none of the aforementioned. Sherald’s ‘Mother’ stands tall, with a stern gaze, a misshapen brimmed straw hat, a casual white short-sleeved T-shirt, with form-fitting blue jeans, while cradling her child on her hip. She is dressed to bend, play, comfort, protect, lift and love her child. To Sherald’s point, here is a mother with a child, worthy of being seen, and lauded, for the physical demands of mothering.

Left to right:

Amy Sherald, Mother and Child, 2016. Courtesy The Blanchard Nesbitt Family. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photograph by Joseph Hyde.

Isis with Infant Horus, Ptolemaic Period, 332-30 B.C.

Benvenuto di Giovanni, Madonna and Child, 1470. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975.

Children are also prominently featured in this exhibit in works such as Well Prepared and Maladjusted to They Call Me Redbone, but I’d Rather Be Strawberry Shortcake to All Things Bright and Beautiful to Kingdom. Cherishing childhood is especially important to Sherald, as it was during this phase of her life when her desire to be an artist was born. It was as a sixth grader, on her first trip to a museum in Atlanta, when Sherald felt compelled to linger at a towering ten-foot-tall painting by Bo Bartlett, Object Permanence. An African American man was a central character in this painting. She had never seen an African American as a protagonist in any artwork before. She credited this painting and museum visit as the moment she knew she would be an artist who painted people who looked like her.

Bo Barlett, Object Permanence, 1986. Courtesy of The Bo Bartlett Center, Columbus, Georgia.

The curatorial choice to present Sherald’s portraits chronologically invites us to witness the evolution of her aesthetic strengths. From backgrounds that were tentative and multi-colored, to decisive single-colored hues. From whispers about the lynchings of the unknown, to outspoken support for a specific victim. From surrealist stories told during the height of her medical crisis; to her post-heart-transplant confidence she exhibited with her portrait of the former First Lady. The subtext and themes of Sherald’s scholarly artistic statements in American Sublime—Politics, Injustice, Sexuality, Womanhood and Children—have masterfully presented African Americans as intrinsically intertwined in all American stories, in unobtrusive, proud and very necessary ways.

Lisa Black-Cohen

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED

Footnotes:

[1] Sherald, Amy, (Artist: American Sublime), The Whitney Museum of American Art, Audio Description.