Beyond Speculation: The Staying Power of Antiquities

In an art world dominated by speculation and spectacle, the Antiquities market is holding its ground—quietly, but stubbornly. As broader economic instability reshapes collecting habits across Impressionist, Contemporary, and design markets, ancient art continues to attract a small but steady stream of buyers. According to Antiquities advisor Judith Nugée, that enduring appeal is rooted in something fundamental about these works: “the primary function of art has always been to tell a story. That thread runs through to today. People still want that connection to something bigger than themselves.”

Judith Nugée of Hornsby + Nugée Antiquities Consultants. Photo Courtesy: Judith Nugée.

Antiquities generally represent the low end of the market—with notable exceptions running into the high end—because they are less reactive to headlines, and therefore less vulnerable to speculation. It is a sector driven less by trends and more by scarcity, scholarship, and provenance. The 2025 Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report shows the sector experienced a drop in sales of a mere 4% last year, a part of the global art market’s overall 12% drop in sales. Dealers in Antiquities and Decorative Art had among the lowest average turnovers. The report acknowledges that the sector “has faced many challenges, with limited supply as well as what some described as a ‘shrinking base of buyers’ every year and numerous regulatory hurdles related to ownership as well as restrictive trade laws within the sector.”

Nugée, a former Head of the Antiquities Department at Christie's, who has served on vetting committees and currently serves as an independent expert advisor to the British Museum’s Treasure Valuations Committee, confirms this. “The low-to-middling market [for Antiquities] is quiet at the moment,” she says. “But the high end, those with strong provenance, is going well.” In other words, quality continues to command attention.

The supply, however, is dwindling. “There’s a shrinking pool of material, and not much well-provenanced fresh stock appearing,” she explains. This scarcity is what has helped to insulate the market, which, unlike flashier sectors, doesn’t depend on “boom” cycles. “Because there are no surges—no boom markets—it remains steady.”

Ancient Jewelry sold at Christie’s 2nd July Antiquities Auction of this year. Photo courtesy: Christie’s.

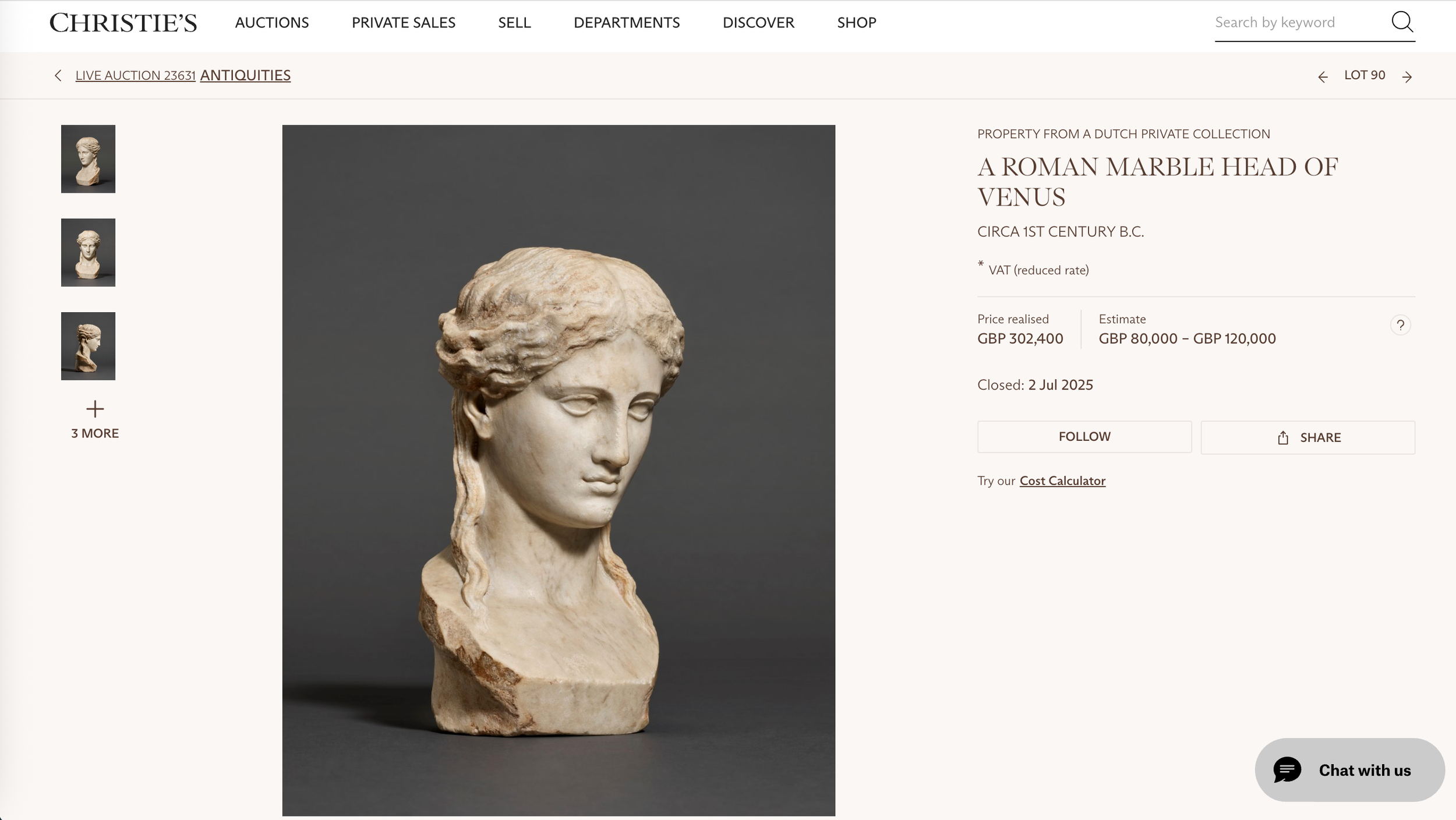

Star lot from Christie’s 2 July Live Antiquities Auction. Photo Courtesy: Christie’s.

One of the most notable developments, says Nugée, is the growing interest from a new type of collector: aesthetically driven, less academic, and often unaware that Antiquities are even available to them. “New buyers, who cause anxiety for most market predictors because of their unpredictability and refusal to follow trends,” she says, “will still buy Antiquities.”

In fact, part of the appeal lies in the surprise, Nugée says. “A lot of new collectors don’t realize that you can buy Antiquities.” After believing the common misconception that that right is only reserved for institutions, “it’s a revelation,” for new buyers to discover they can own an Egyptian shabti or a Roman pendant. That moment of discovery becomes a key driver of engagement. The idea that something they’ve only ever seen behind glass at a museum is actually accessible—even ownable—has a powerful emotional impact.

Many of these collectors are in the middling stages of their lives, and they want pieces that are both beautiful and meaningful. “People who remembered something from school, or saw something on a trip—they’re surprised,” she says. “They still want to be surrounded by beautiful things.” For this new generation of buyers, the visual punch and historical resonance of an artifact matter more than its academic context.

Crucially, this aligns with larger cultural shifts. “The experience of antiquities gives it its value,” Nugée says, “and we are in an experience economy.” Buyers are less concerned with possession in the traditional sense and more focused on the emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual experience that comes from engaging with an object of the past.

Some institutions are capitalizing on this desire to experience the antique past in new ways. The underwater Cosquer Caves of Marseilles, for example, have long been a site to visit if one wants to view prehistoric cave paintings up close. Today, however, the site is under threat of flooding due to rising sea levels, making the already hard-to-access historical landmark even more perilous. As of June 2022, an immersive replica of these caves opened at Villa Méditerannée, allowing visitors to experience the caves ‘underwater’ via exploratory vehicles without having to obtain their diving license first. The experience is likened to that of theme-park-meets-museum, but certainly makes learning about our mysterious Prehistoric past more accessible. And this education, in turn, keeps the prospect of owning a piece of our history exciting.

Visitors take in the immersive experience of the recreated Cosquer Caves at Villa Méditerannée. Photo courtesy: Grotte Cosquer.

Provenance has become a major talking point in recent years, and is now something which can significantly add or detract from value. Especially since 2000, when US regulations became more defined. Well documented provenance is essential for high-value institutional or museum level acquisitions. But there is a more nuanced approach for the average buyer, argues Nugée. Some, new to collecting, are completely unaware of the provenance issue, which is problematic.

“It has become more of an issue in recent years, but people can still collect actively and responsibly. The market is healthy.” Among the high-end, provenance is still a decisive factor, and vetting committees, she notes, are becoming more rigorous: “Getting stronger, because people care more about provenance.”

Still, what drives most buyers—especially newer ones—isn’t a dossier of legal documents but the visual and emotional appeal of the object itself.

As museums increasingly strive to tell socially relevant stories, antiquities have found new resonance. At Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, the new Roman wing focuses in part on slavery in the ancient world—a reflection of broader curatorial shifts. “There’s this ‘box-ticking’ impulse,” Nugée says, “but it’s also a chance to look deeper.” Antiquities offer not just aesthetic pleasure but entry points into cultural conversations.

Meanwhile, younger collectors, who are often less academically informed, still respond to the emotional weight of an object. “Aesthetics are more important to buyers and even to museums now,” says Nugée. “The population is less informed, so the work needs to have aesthetic punch, or a wow factor.”

Even trends in Contemporary art can trickle into the Antiquities market. When a modern artist engages with Classical themes, such as when drawing from sculpture, architecture, or ancient myth, it brings new audiences into the fold. “A Contemporary audience is brought in when a Contemporary artist focuses on a Classical piece,” she notes.

For example, Michael Rakowitz's The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist was unveiled on the Fourth Plinth in London's Trafalgar Square in March 2018: a replica of the Assyrian Lamassu, or human-headed winged lion sculpture. Two Lamassu feature in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, great beasts which stood guard of the ancient city of Nimrud in modern-day Iraq. Rakowitz’s 2018 Lamassu was accordingly created out of 10,500 Iraqi date syrup cans, in an attempt to recreate one of the over 7,000 objects looted from the Iraq Museum in 2003 or destroyed at archaeological sites across the country in the aftermath of the war. Accordingly, the same year the Trafalgar Square plinth was unveiled saw a record-setting sale of an Assyrian relief at Christie’s.

Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, 2018. Photo Courtesy: ArtUK, Caroline Teo / Greater London Authority.

For seasoned buyers and new collectors alike, Antiquities represent more than just a category. They’re a point of contact with the past. A recent example of this shift in presentation came from Charles Ede, the London-based antiquities dealer, whose exhibition of Roman glass included a collaboration with a florist. The ancient vessels were filled with fresh flowers and displayed as they might appear in a domestic setting, offering a striking reminder that these objects were once everyday items, not just museum pieces. The goal wasn’t just to sell artifacts, but to help visitors imagine how antiquities could function in contemporary interiors. It was a deliberate nod to modern taste and lifestyle, making the ancient feel accessible, even personal.

“If you buy something because you love it, chances are it’s a good investment,” Nugée says. In a market where surges are rare, steady value is the reward for patience and taste.

Installation shots of Roman Glass at Charles Ede. Photo courtesy: Mairi Alice Dun.

The resilience of Antiquities lies not only in their age, but in their ability to remain relevant—to speak across time. As Nugée puts it: “As humans, collecting is something we do and what we have always done, for millennia. Collecting Antiquities has been going on for centuries; today it gives us the opportunity for a direct and visceral connection to past civilizations as well as to our history, to our past, to what makes us who we are.”

In an economy driven by experiences, Antiquities offer something unique: ownership of a piece of the past. That continues to matter, even in a downturn.

Many thanks to Judith Nugée on behalf of MADE IN BED.

Mairi Alice Dun

Editor-In-Chief, MADE IN BED