Innocence of the Eye: what artists and galleries can learn from children

When twenty-two year old Paul Klee returned home from art school in 1901, he revisited his childhood sketches only to discover that his best work had been created in his first decade of life, years before his artistic training at the Munich Academy. Klee included these early works in his self-compiled catalogue raisonné, not because they were particularly technical, in fact they were rather rudimentary sketches similar to those we all produced as children, but because they revealed an inner certainty. Klee’s childhood drawings were made up of simple shapes, with little concern for depth, proportion, or space. This is because representing objects “correctly”, according to how they appear in nature, is something imposed from external logic rather than guided by inner certainty.

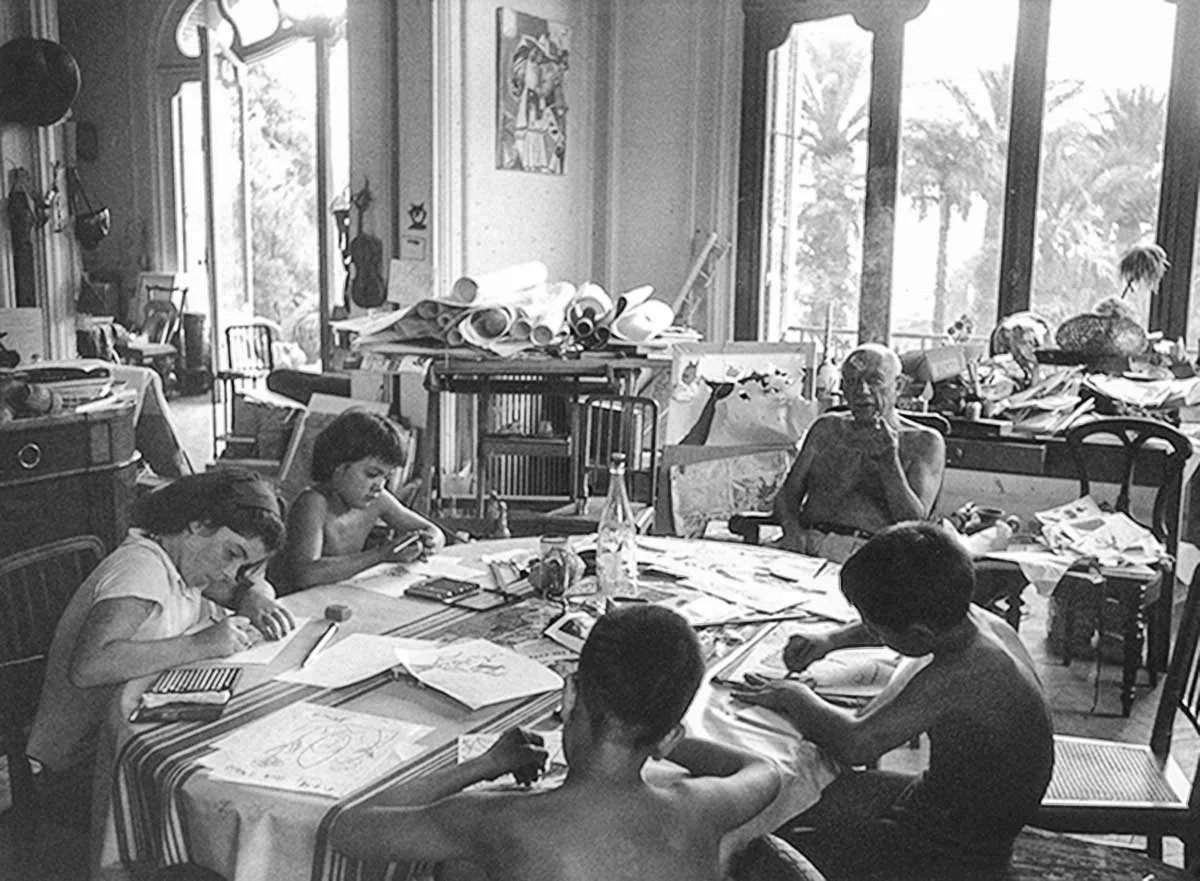

It was precisely this inner certainty, and the ability to move beyond the visual cliches of past art, that Klee aimed to recapture in his mature work. Victorian artist and critic John Ruskin termed this the “innocence of the eye” and encouraged artists to represent nature with the vitality of a child who, as reiterated by Baudelaire, “sees everything in a state of newness”(Turner, “Through the Eyes of a Child,” Tate Etc.). Picasso, too, was deeply fascinated by children’s art. Having been steered towards an academic style from a young age by his father, a drawing professor, he later sought to reclaim the spontaneity of his early creative instinct. While touring an exhibition of children’s art in 1956, Picasso told poet Herbert Read, “When I was the age of these children, I could draw like Raphael. It took me many years to learn how to draw like these children” (Bretton, “Why We Need to Take Child Art Seriously.” Royal Academy of Arts). It is not just children’s ability to capture the world on paper that has fascinated artists, their ability to imaginatively respond to their environment through play has been taken up by creatives.

Pablo Picasso giving a drawing lesson to his children Paloma and Claude, and two friends. Photograph by Rene Burri / Magnum. Photo courtesy: Stedelijk Museum.

Since 1999, the Belgian artist Francis Alÿs has documented children playing in public spaces around the world. He presented this work, titled The Nature of the Game, at the Belgian Pavillion of the 2022 Venice Biennale. Alÿs argues “whereas adults are more likely to use speech to process experiences, children play to assimilate the realities they encounter” (Alÿs, The Nature of the Game. WIELS Contemporary Art Centre). Alÿs’s installation argues for play as a creative response to circumstance; an inventive exploitation of the given environment.

Francis Alÿs, Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack. Hong Kong, 2020. Courtesy of WIELS.

None of these artists are alone in their desire to archive the creative products of children yet on the flip side, many galleries and visual arts institutions struggle to create spaces that embrace playfulness and collaboration—spaces that allow the outside in. The clean-cut white cube gallery space so closely associated with 20th century art isolates the artwork from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself. In contrast, spaces accessible to children are designed to foster interaction and experiential learning. These environments encourage active participation in the creative process, allowing children the opportunity to not only engage with art but to see themselves as producers of it. This approach challenges conventional notions of spectatorship and authorship, concepts that many adults, conditioned to view art as something to be passively observed in a vacuum, may find disconcerting.

The Young V&A offers some of the most sustained examples of this new approach, with spaces designed at a child’s scale and exhibitions built around tactile exploration. In Make It: Fashion, children can design and model their own garments, while Design and Draw with Light invites them to manipulate illuminated drawing tools in a sensory-friendly environment. Open studio spaces remain deliberately unstructured, allowing children to experiment freely with materials, much like Klee’s earliest creative experiments.

Jenny Pengilly, Popcorn!, 2025. Photo: Anne Tetzlaff. Courtesy of: Whitechapel Gallery

The Whitechapel Gallery’s current participatory exhibition Popcorn!, by artist Jenny Pengilly, transforms the space into an interactive and imaginative sound world, where families can create Foley effects and experiment with sonic textures in DIY studios. This multi-sensory exhibition invites all audiences ensuring that creative play is integrated rather than siloed as a “children’s activity.”

Even the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern has become an annual site for collective, intergenerational creation. Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room (2022) began as a blank white interior which, through the gradual layering of millions of dot stickers applied by visitors, evolved into a collaborative sea of colourful dots. In 2024’s The Flooded Garden, Oscar Murillo invited participants to paint and move across enormous canvases, their footprints and gestures becoming part of the final work. These installations were not just “child-friendly”, they offered every visitor the chance to rediscover the vitality of spontaneous mark-making.

Oscar Murillo, The Flooded Garden, 2024. Courtesy of: Tate

The growing popularity of collaborative and sensory-led installations reflects a wider cultural shift. As museums compete for public attention, environments that stimulate multiple senses and encourage active participation are attracting broader audiences, including those who may never have considered stepping inside a gallery. Crucially, spaces designed with young people in mind often become more accessible for everyone. While public institutions are increasingly moving beyond the static, white-cube model, the commercial art world has been slower to follow. Art fairs and galleries still largely operate as quiet, high-stakes environments, resistant to the creativity and curiosity that participatory work can generate. Yet the success of projects at the Tate, Young V&A, and Whitechapel suggests that embracing play is not a niche concern but a vital strategy for cultivating future audiences. If, as Klee, Picasso, and Alÿs have recognised, art’s power lies in sustaining the openness and inventiveness of childhood, then the challenge for institutions is clear—to design spaces where everyone can create, explore, and actively experience art.

Nina Mangion

Features Co-Editor, MADE IN BED