Whitney Biennial 2022: Process as Much as Product

Years of global crises have passed by and unyieldingly tested the art enthusiast’s patience. The viewer yearns for the real thing, for a visceral experience, a space to engage and reflect, and a community with whom to share their perceptions. In the Whitney Biennial’s 2022 catalogue forward, Whitney Museum of American Art Director Adam D. Weinberg reflects on the importance of such in-person living, even in the face of an increasingly digitised (art) world.

‘Lush conceptualism’ is a central approach to this biennial, where artists confront rich, bold ideas, debates, and contested subject matter through artistic practices that explore everything yet impose nothing. The viewer has the tools and material to consider and reflect independently, with interconnecting disciplines and symbiotic practices to guide their thinking, thus reinforcing a mindfully present and physical manifestation of ideas.

Presented over three instalments, MADE IN BED’s Whitney Biennial 2022 series will focus on the three key narrative threads that run throughout the extensive group show in New York.

Matt Connors, Body Forth, 2021. Oil on canvas.

The Whitney Biennial 2022 is comprised of four floors, including the ground floor and the terrace, and engages the work of sixty-three artists across painting, film and video, photography, installation, sculpture, and dynamic combinations of all of the above. A group show meant to reflect on the art-historical context and socio-political and cultural significance of the preceding two years and delayed due to Covid-19, the pandemic, race relations, and climate change were dominant themes in the minds of the artists, curators, and prospective visitors. But the undercurrent of such monumental themes truly lies in internal and self-reflection, relationships with others and identifications with other cultures, and the wider global issues that challenge us to engage with and confront the future of our planet as a whole. All sixty-three artists, each through their unique practices, consider these themes through this biennial, but above all the curators have discerned the relations between these three concepts within experience and relationships. Although the artists explore their relationships with themselves, their communities, and the wider world, rarely is any work isolated in these themes. The divine characteristic of collective reckoning is the fluidity of all three and how often they symbiotically behave.

Woody De Othello, study for The will to make things happen, 2021.

The first curatorial foci in this trifecta consider the dimensions of the self and the complexities of intellectual and emotional processing, memory, dream states, and reckoning. Bold abstract painter Matt Connors considers this process of reflection in self-discovery and identity; focusing on the actions of thinking and acting as opposed to exclusively fixating on the result. In his work, he is creating the conditions for the work. A striking oil on canvas entitled Body Forth (2021) uses components, organic forms, and intricate assemblages to drive the shape from right to left across the canvas in a complicated yet synchronised flow of movement. The power lies in the artist’s construction of form, for the completed entity will decide its own direction. Such a process equips the Biennial viewer with the ability to employ process and framework to the subsequent themes of the internal and the self-driven.

Several works in the Biennial employ this focus on process to explore how our bodies might engage with the altered world around us, and the material we use to communicate this understanding. Woody De Othello found clay to investigate this, regenerating the approach to the material in order to give life to personal experience. Study for The will to make things happen (2021) reflects on the vulnerability induced by the pandemic, and the careful negotiation between risk and exposure with a degree of caution in mind.

Emily Barker, Untitled (Kitchen), 2019. PETG plastic cabinets, rivets, wooden base. Photo by Josh Schaedel.

Self-questioning and consideration lead us to face what dominant societal norms we take for granted and what we’re challenged to question and renegotiate. Emily Barker’s Untitled (Kitchen) (2019), a reconstructed system of cabinets and countertops, reintroduces an all-too-familiar domestic scene that in fact subscribes to standardised production and building codes that exclude those with disabilities and limited access to such a design. With a changing world and precariousness of the health care system during a global crisis, the viewer must confront their role within their own physical reality.

Jacky Connolly, still from Descent into Hell, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

What physical reality is and how and what is experienced is considered by Jacky Connolly in her video work entitled Descent into Hell (2021). Doris Lessing’s 1971 novel Briefing for a Descent into Hell imagines the fantasy life of an amnesiac who has wound up at a psychiatric hospital. The body in the hospital is confined to a bed, whilst the man is elsewhere, sailing on a raft, or floating into outer space. Through multichannel installation, Connolly investigates a similar alternate reality, using the diversity of her medium to explore dimensions and states of ‘being.’ With a surge in vivid dreaming reported during the pandemic and an increasingly digital existence taking shape, the viewer is encouraged to consider what and where real meets imaginary, and whether the boundary matters at all.

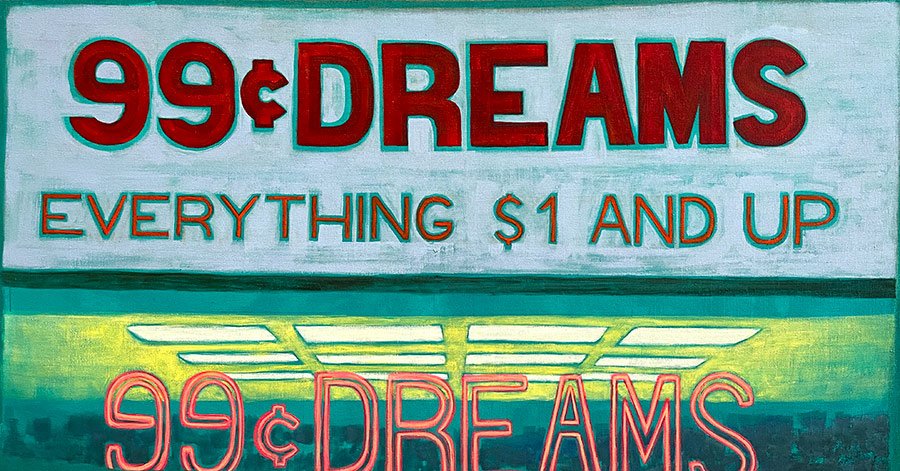

Such a question of lived reality is further investigated in Jane Dickson’s work, as she reflects on a professional phase of her life when she worked as an animator in the 1980s in New York. During the pandemic, the artist reflected extensively on this period, when New York City was burning, suffering also from great economic devastation and the onslaught of the AIDS crisis–its own pandemic–and subsequent repercussions. Through the connection of two phases of her life and reflecting on similar recurrences, Dickson observes the materiality of time, the dimension that shifts between the then and now, and the significance of acknowledging these nuanced bridges of existence. Works like Save Time (2020) and 99¢ Dreams (2020) reference mass media imagery and stylisation that summons the memory of another era. The viewer is encouraged to consider the role of the laundromat, how time might be simultaneously saved by efficiency and lost through waiting and to remain cognizant of how then and now might intertwine. Like Connolly’s foray into the imaginary, Dickson also carves out a new landscape for exploration.

Kate Fensterstock

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED