Whitney Biennial 2022: Process as Much as Product

The internal complexities of self-recognition and eventual action are key components to how the Whitney Biennial 2022 artists build connections with greater sociocultural issues that continue to affect themselves and the lives of others. But what happens when the figurative cultural nuances and, eventually, the physical consequences of our actions become too big and complex to understand and almost impossible to negotiate?

In the final instalment of MADE IN BED’s Whitney Biennial 2022 coverage, its third narrative component thematically considers the environment and climate. More specifically, it investigates how the Self–having engaged one’s own methods of processing and purposeful action–might engage with and understand cultural and communal relationships to ultimately navigate the greater unknown.

Leidy Churchman, The Between is Ringing (Milarepa’s Biggest), 2020. Oil on linen, 177.8 x 142.5 cm. Photo by Lewis Ronald. Courtesy of the artist and Rodeo, London/Piraeus.

Several artists in the 2022 Biennial fervently explore what is inherently challenging to grasp, how we might use what we know as a lens to attempt to process such material, and how we might then reject these frameworks and regroup to embrace original thought and engineering to design a whole new future. Leidy Churchman views painting to be the only constant in a world that we’re not able to fully comprehend. It’s a tool for embarking on the unknown, but is its own entity at the same time, uncompromised and uncontrolled by its artist or its viewer. In The Between is Ringing (Milarepa’s Biggest), Churchman appears to be exploring the organic and fantastical form as well as an abstract investigation of space. The human-like figure appears to be venturing into a dimension behind the canvas, indicating an artistic observation of depth, yet creating a concrete narrative whereby the figure is absolved by a monstrous animal-like form. This work displays the diversity of a two-dimensional medium, and how the artist investigates its dimension in handling complex modes of expression.

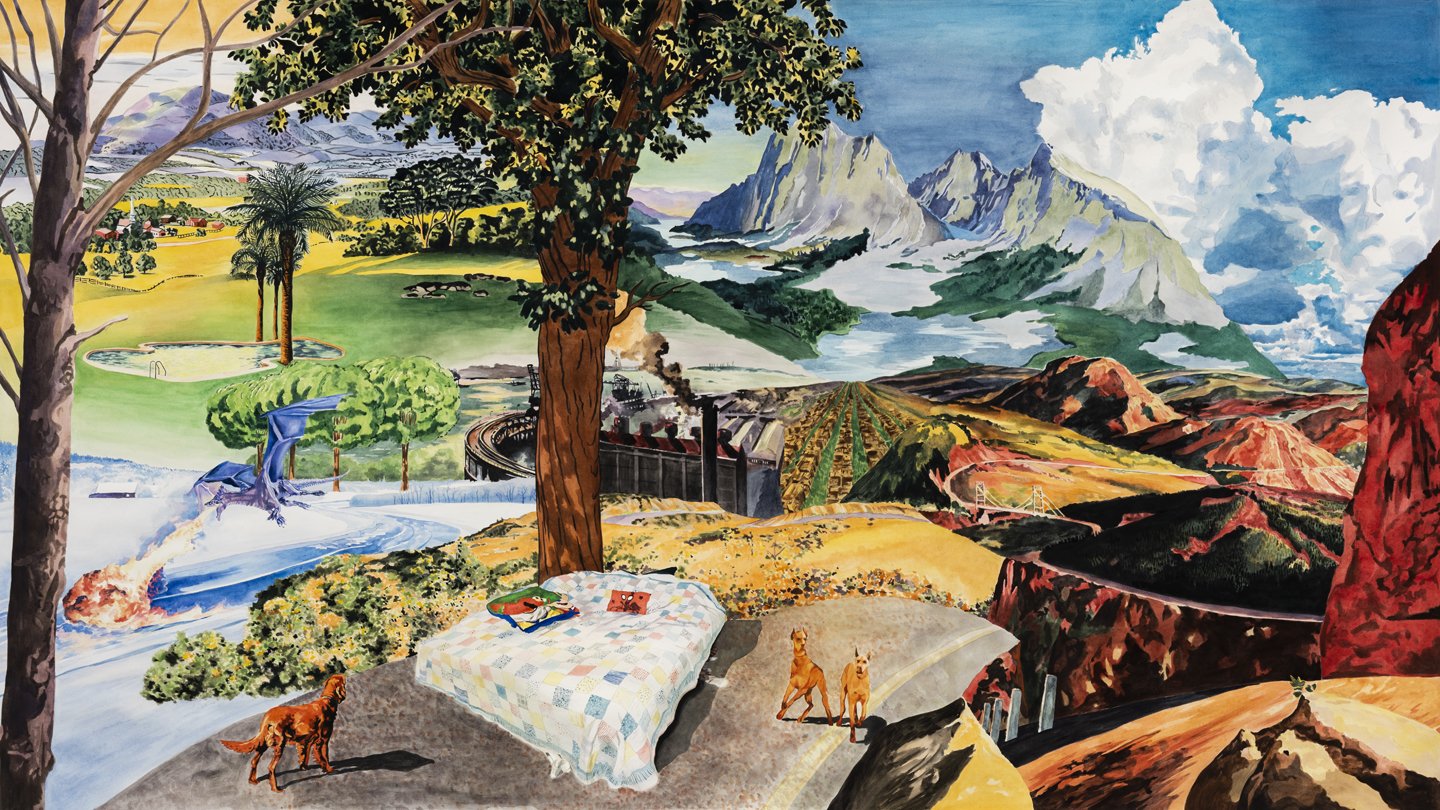

Danielle Dean, 6. a.m., 2020. Photo courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal, New York.

Danielle Dean considers how icons of past and present culture might help us grapple with mammoth issues including globalisation, transport, and pollution. Whilst living in Detroit, Dean became fascinated by the presence of the Ford automobile, and specifically how landscape is represented in relation to the car as a consumer product; the way representations of landscapes have shaped our collective consciousness with the human at the centre and how this connects with the reality of extraction from actual landscapes of car production. Her video work entitled Long Low Line (Fordland), which is redrawn and painted in the form of Biennial works entitled 6 a.m. and 5 a.m., depicts the company town Fordlandia that was set up in the Brazilian Amazon for the extraction of natural resources, specifically rubber, for car production. Such repainting and repurposing emphasise reconfiguring and reworking our perspective on what we try to understand. The landscapes are bright, luscious, and almost idealistic images of the natural world that simultaneously feel empty and soulless, with no people visibly present. The scene has an artificial quality and exists somewhere between the past, present, and future, taking significant culture linchpins such as Fordlandia and assembly line production to design a foreboding alternate reality.

Alia Farid, Palm Orchard, 2022. Photograph by Shaye Weaver/Time Out New York.

Alia Farid inverts this concept, observing how nature is used to further or substantiate human interest. Growing up in Kuwait, Farid reflects on how colonial forces would divide entire regions, bifurcating communities and their relationship to the land. When water was inaccessible without expensive desalination plants on home turf, this natural resource became a pawn in foreign policy. Only when Kuwait began to financially succeed from oil could there be freedom to access water locally and guaranteed political isolation from Iraq which had supported their interest beforehand. Farid’s work Palm Orchard features artificial palm trees made from mechanical, industrial materials that render them weaponised, emphasising the ransomed character of nature amidst these political debates, whereby humans exploit nature to further our own interests.

An invitation to an event presenting Dispatch featuring Raven Chacon and Candice Hopkins.

Co-authored by artist Raven Chacon and curator Candice Hopkins–and the third of the pair’s co-authored scores–Dispatch (2020) breaks down a three-component strategy aimed at protecting the Navajo nation landscape at risk due to development and resource plundering through a practice focused on reverence, collective power, and action. Hopkins references the first three lines of the score in her accompanying catalogue essay in response to actions by water protectors at Standing Rock to halt the expansion of the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016: “This rock is under threat/We need to gather here to protect it/Our actions begin and end at this place.” The project details imagery, schematics, and manifestos which communicate and direct how and where to protect the sacred land that needs help. It’s through reflection, connection, community effort, and strategic methodical action that Hopkins pursues the protection of the natural world.

Wangshui, Weak Pearl, 2019. Photo by Alwin Lay.

A recurring observation amongst the artists in the Biennial is to not ignore the past as it informs the present. It’s imperative and largely required that what has been will inform what will be. WangShui explores the post-human perception of generating new matter and physicality from a collective consciousness of the existing human, animal, environmental, and machine registers. The work consists of LED engineering that generates AI flesh from live data and brushed aluminium paintings co-produced with neural networks. The surfaces refract the generated material resulting in organic chaos and confusion. The work is both regenerating our known states and forecasting an alternative existence only to substantiate existing realities such as chaos and confusion.

Wangshui, Weak Pearl (detail), 2019. Photo by Alwin Lay.

The cyclical trend in the Biennial of past to present, the self to the collective, and the known and the unknown is a strong current that boldly flows through the diverse groupings of contemporary practice. Although there are three distinct approaches to the internal, the relational and the wider unchartered can be identified and unpacked with careful precision. The Whitney Biennial 2022 simultaneously unifies each work together in a symbiotic cultural ecosystem from which we’re sure to learn a great deal about where we’ve been and where we’re going.

Kate Fensterstock

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED