‘ARTE POVERA / Postwar Italian Art’ @ The Margulies Collection in Miami

Paired with the soaring concrete frame of The Margulies Collection’s Warehouse, ARTE POVERA / Postwar Italian Art symbiotically works with the quintessential challenge to traditional materialism that the movement presents.

‘Arte Povera’ refers to this shift in technique, but most crucially in the face of the postwar cultural crisis where the work equally reflects on shifts in everyday ‘Italian-ness’ following the impact of the Second World War, thus redefining the position of the Italian artist in the face of sleeker, more refined examples of traditional Minimalism.

The collection’s longtime lead curator, Katherine Hinds, selected works from this period that consistently reflect mindful employment of new and challenging material whilst negotiating a changing and evolving sense of personal, artistic, and cultural Italian identity.

Exterior view of The Margulies Collection in Miami, Florida. Photo by Kate Fensterstock.

ARTE POVERA / Postwar Italian Art is right at home within the 50,000 square foot Warehouse infrastructure of The Margulies Collection–one of the most esteemed private collections in the world. The collection is renowned for its photography, video, sculpture, and installation works, many of which embody large-scale, grandiose features in the style of Richard Serra, Anselm Kiefer, and Donald Judd, whose materialism bodes well in such a heavily industrial architectural space.

Pier Paolo Calzolari, Untitled (Cinghe), 1971. Leather, refrigerating unit and copper pipes, neon, transformer, lead, 330 x 149 x 35 cm. Image courtesy of The Margulies Collection.

The exhibition features two galleries distinguished by the light installation objects exclusively installed in one black-walled gallery which provides the best visibility for the electric objects to glow impactfully. The extent to which neon light was a key component of quintessential Arte Povera practice is abundantly clear and of great interest to Margulies, who has a Dan Flavin installed in an adjoining permanent exhibition. The material is frequently used in order to explore expanded limits of communication and push concepts and transmit ideas with a technologically advanced call to action. In Pier Paolo Calzolari’s Untitled (Cinghe), the artist incorporates neon lettering against the rigidity of the straight copper form and the softer flexibility of the leather straps, using differentiating materials to embolden their individual impacts. The staircase references ascension and descension, personal mobility, and progression of a social unit, as well as acknowledging a quest for higher consciousness arguably achieved through a higher means of communication [through new material].

Michaelangelo Pistoletto, Two Less One, 2009. Golden wood and mirror, each 180 x 120 cm. Image courtesy of The Margulies Collection.

The purposeful use of material to explore notions of identity is pursued most blatantly by Michelangelo Pistoletto in Two Less One, where a pair of large mirrors in gilt frames have been smashed. Two Less One preceded the famous performance where the artist smashed multiple mirrors as part of the 53rd Venice Biennale. In the artist’s own words, the mirror acts as a universe of time and space, infinitely reflecting back all that exists forever. When this sphere is smashed, the shards become multiplied particles of smaller dimensions that also infinitely reflect, record, and perpetuate every action that will become a memory. Pistoletto’s focus here is the functionality of a mirror to capture what goes on around it, employing its physical nature, reflection, and fragility to generate a tool that inherently engages with our choices and actions.

Gilberto Zorio, Senza titolo (Stella), 1990. Copper star on tar background. Photo by Kate Fensterstock.

Further, Gilberto Zorio’s practice is often an investigation into how natural processes function, such as alchemic reactions and the transfer of energy. His work entitled Senza titolo (Stella) features a five-pointed star made from copper on a tar background. The star is a recurring motif used by Zorio to signify the transfer of energies, particularly from those created during alchemic processes whereby copper and tin can turn to gold and silver. This activity is made more significant considering copper, tin, and tar are used for industrial and utilitarian purposes. This negotiation is reforming the substances’ materiality–a pillar of the Arte Povera ethos. Such a definition is echoed in this work, which takes the form of a flag or icon, a symbol of national presence that is perhaps reconfiguring its own sense of meaning and purpose.

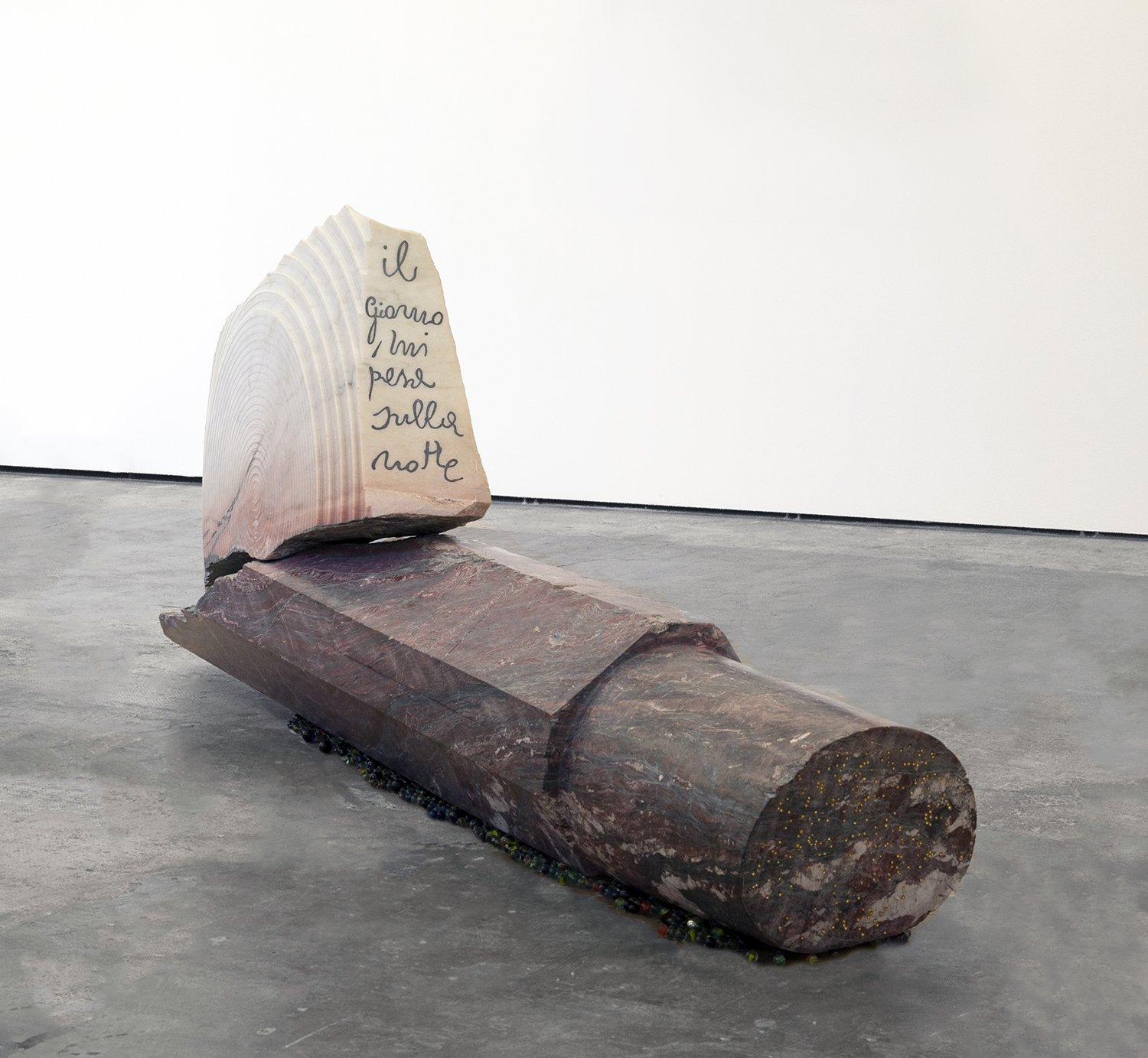

Luciano Fabro, Il giorno mi pesa sulla notte I, 1994. Portuguese pink marble, red Levanto marble, gold, lead, glass, 100 x 256 x 37 cm. Image courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Zorio’s utilisation of industrial copper and tar and their alchemic relationship, plus the emblematic imagery of the star, provides a more literal investigation of materiality and identity that is explored throughout this exhibition. Such works seem to provide a physically central anchor to the show’s curation, with the Zorio at the front of the first gallery and in the centre of the same room. Two Fabro sculptures provide a similarly literal interpretation of how material and identity might be treated in the Arte Povera discipline. In Gli amanti (nudi), two curved slabs of marble sit on top of one another, placed on the floor. The use of marble, a quintessentially Italian material that plays a key role in the history of art, is drastically reimagined with the use of a more modern form, exuding a conceptual figuration and interrogating the changing nature of “Italian-ness” in quite a straightforward way. His second sculpture in the exhibition, installed adjacent to Gli amanti (nudi), is entitled Il giorno mi pesa sulla notte, translated to mean ‘day weighs on my night.’ The title is inscribed on a piece of marble, again referencing historic significance dating back to the Italian classical period, but directly poses certain existential questions concerning order, image, and how knowledge is the key to understanding and a wider universe. In both works, Fabro is inherently employing a quite literal reconfiguration of traditional material to question notions of change and differentiation in the late 20th century, using his practice to make this change through carving and figurative reconstruction.

Luciano Fabro, Gli Amanti (nudi), 1987-1988. Marble, in two parts, 17 x 246 x 45 cm. Image courtesy of The Margulies Collection.

These five works exemplify how the exhibition shows artworks that each embody a fascinating balance between reconsidering materiality in Italian art and how such an investigation might allow for a reexamining of the notion of identity in postwar culture. Such a dive proved to be a key component in building the exhibition and a vital part of understanding and engaging with the strength of such an art movement. These two concepts of how to treat material blended with conceptual identity theory, which appear inherently different, do in fact work together to reveal a more nuanced reality of the Arte Povera condition.

To learn more about The Margulies Collection and ARTE POVERA / Postwar Italian Art, visit their website.

Kate Fensterstock

Contributing Writer, MADE IN BED